José Francisco Borges (Brazil, b. 1935) is considered one of the foremost woodcut artists in Brazil, and he got his start making cover designs for cordel literature (about which you can read a previous post here). His editions are not limited and vary widely because he continues to print popular images repeatedly, as well as modifying or recarving blocks over time. He also prints blocks in both black and white and color. He is a definitely a folk artist, despite having been embraced by the art world. Perhaps because of his cordel roots, Borges gives all his work a banner across the bottom with the title and his name.

His work depicts a wide variety of subject matter, but today I’m sharing a sampling of his fantastical creatures. In addition to lots of depictions of the devil (my favorite title is “The Woman who Put the Devil in a Bottle”), and mermaids, Borges loves to depict dragons. His dragons, however, are not generally very close to the typical modern western version I imagine. Some are more humanoid, some are called “serpents,” and relatively few have wings. All are bold and spiky and inclined to a certain lumpiness.

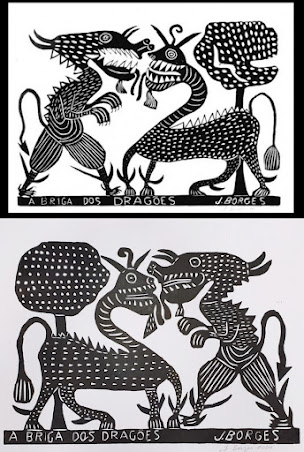

I had trouble limiting myself when there were so many I liked, so I’ll just say a brief word about each of these. The two block prints at the top show how Borges revisits designs. My assumption is that the top version was first, and the second version is reversed because it was copied onto a wood block from the first (and simplified along the way.) The top right dragon is especially delightful to me!

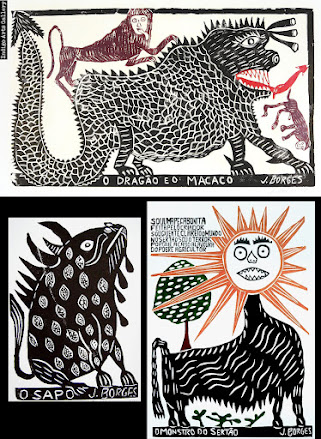

Next up is a very unusual serpent. It has only hind legs and no wings. Although I always tend to be inclined toward black and white, in this piece it’s definitely the color that makes it pop. I love the pattern on the snaky body. Then the next dragon isn’t snaky or even very reptilian at all. It almost seems more like a monstrous monkey with its upright posture and hairy texture. But all the spikes and horns and that arrow-tipped nose ensure that it’s something fantastical.

The next piece is in some ways the most classic dragon, especially when you look back a few hundred years to when legless dragons were more common. I love its coils and spikes. It’s followed by a monster with 7 unique heads, which puts the Lycian chimaera to shame. Not only does this have goat and snake heads, but also lizard, chicken, bull, human, and maybe another goat. Plus it’s got wings like leaves and a tail like a spatula!

And then comes the lumpiest dragon of all, with more carefully carved scales than any of the others, spikes everywhere, and three stalks on its head that I would love to think are extra eyes (although I’m guessing Borges probably didn’t intend that). I also give you a creature entitled “frog,” but clearly no ordinary, everyday frog! And finally an interesting sun-faced monster. Living in the northeast in January, I think of the sun as a benevolent and welcome creature, but in the Sertão region of Brazil where droughts are common and deadly, it is seen as a monster.

What do you think of these dragons, serpents, and monsters? I certainly wouldn’t want to meet any of them in real life, but in block print form they really cheer me up!

[Pictures: The Fight of the Dragons, two versions, wood block prints by José Francisco Borges, second version dated 2020 (Images from Pinterest and Cestarias Regio);

Fight Between the Jaguar and the Snake, wood block print by Borges, 2003 (Image from Arte Popular do Brasil);

The Dragon, wood block print by Borges, 2005 (Image from Indigo Arts Gallery);

The Serpent, wood block print by Borges, 2003 (Image from Arte Popular do Brasil);

Beast of 7 Heads, wood block print by Borges (Image from Mirabile);

The Dragon and the Monkey, wood block print by Borges, 1994 (Image from Indigo Arts Gallery);

The Frog, wood block print by Borges (Image from flickr Galeria de Gravura);

The Monster of the Sertão, wood block print by Borges (Image from Mariposa).]