Today I have excerpts from three merfolk poems to share. They’re all too long to repeat in full, and they’re all rather wordy and repetitive anyway, so I thought I’d just give you some of the highlights from each. The first two are a pair by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (UK, 1809-1892) and come from his first solo collection of poems published in 1830. Entitled “The Merman” and “The Mermaid,” they share the same structure, and each begins with the question “Who would be a merman/mermaid… on a throne?” The poems then proceed into a fantasy of the carefree lives of the merpeople, concerned only with frolicking about and flirting with each other. The mermaid dreams of being loved by everyone, while the merman dreams of kissing all the mermaids. It’s fluff, but there are some fun descriptive passages.

There would be neither moon nor star;

But the wave would make music above us afar —

Low thunder and light in the magic night —

Neither moon nor star.

We would call aloud in the dreamy dells,

Call to each other and whoop and cry

All night, merrily, merrily;

They would pelt me with starry spangles and shells,

Laughing and clapping their hands between,

All night, merrily, merrily,

But I would throw to them back in mine

Turkis and agate and almondine…

Till that great sea-snake under the sea

From his coiled sleeps in the central deeps

Would slowly trail himself sevenfold

Round the hall where I sate, and look in at the gate

With his large calm eyes for the love of me.

The first excerpt is the merman’s fantasy, and I particularly like the image of “low thunder and light in the magic night” far beneath the surface of the ocean. The second bit is the mermaid, and I like her description of the sea serpent “with his large calm eyes.”

For a different take on merfolk lore, here’s “The Forsaken Merman” by Matthew Arnold (UK, 1822-1888), which is from this poet’s first published collection as well (1849), which may imply something about how sober, serious elderly poets don’t write about merfolk! At any rate, this poem reverses the common folktale trope of a human abandoned by a wife from one of the magical races. (See a prior post for some of the ways this usually plays out in selkie lore.)

Children dear, was it yesterday

We heard the sweet bells over the bay?

In the caverns where we lay,

Through the surf and through the swell,

The far-off sound of a silver bell?

Sand-strewn caverns, cool and deep,

Where the winds are all asleep;

Where the spent lights quiver and gleam;

Where the salt weed sways in the stream;

Where the sea-beasts, ranged all round,

Feed in the ooze of their pasture-ground;

Where the sea-snakes coil and twine,

Dry their mail, and bask in the brine;

Where great whales come sailing by,

Sail and sail, with unshut eye,

Round the world for ever and aye?

“The sea grows stormy, the little ones moan.

Long prayers,” I said, “in the world they say.

Come,” I said, and we rose through the surf in the bay.

We went up the beach, by the sandy down

Where the sea-stocks bloom, to the white-wall’d town.

Through the narrow paved streets, where all was still,

To the little grey church on the windy hill.

From the church came a murmur of folk at their prayers,

But we stood without in the cold-blowing airs.

We climb’d on the graves, on the stones worn with rains,

And we gazed up the aisle through the small leaded panes.

She sate by the pillar; we saw her dear:

“Margaret, hist! come quick, we are here.

Dear heart,” I said, “we are long alone.

The sea grows stormy, the little ones moan.”

But, ah! she gave me never a look,

For her eyes were seal’d to the holy book.

Loud prays the priest; shut stands the door.

Came away, children, call no more.

Come away, come down, call no more.

There are a few interesting points about Arnold’s story. For one thing, the human woman has gone down into the ocean to be with the merman (I like the description of that underwater realm in the first excerpt). But it’s when she hears church bells that she returns to the land for fear that she’ll lose her soul with the merfolk. For another thing, the merman is caring for the children as a single father and he obviously really loves and misses his wife. The church is slightly ambiguous - it’s blinding a mother to the love of her husband and the needs of her children, even as it is a holy place where she sings joyfully. Finally, although the poem ends with the merfolk “left lonely forever,” we do catch a glimpse of the human woman gazing out at the sea with a sigh and a sorrow-laden heart, missing her children. It seems to me that her departure from the ocean looks a lot like Beauty leaving the Beast: she says she needs to go home, and he tells her to go, but to come back. Once she gets there, she seems to forget all about him. In Beauty and the Beast of course she does return at the last possible moment, and save the Beast and live happily ever after. Do you think there’s a chance that could happen for this family, as well?

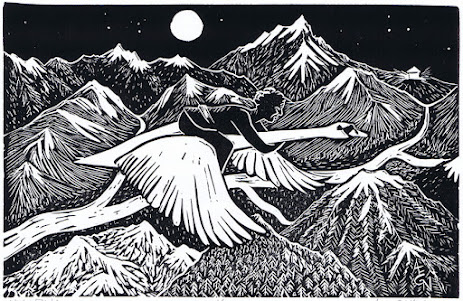

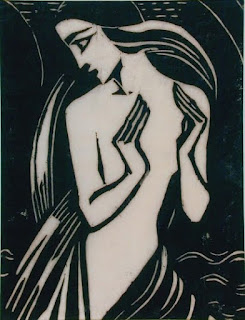

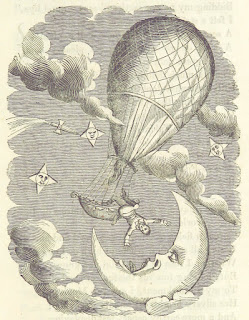

[Pictures: Mermaid, color woodcut by Russian artist whose name I can’t make out because it’s in Cyrillic, 1915 (Image from StardustPrintShop);

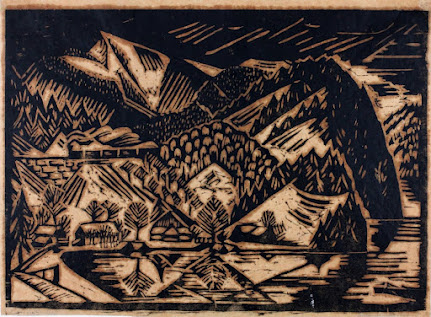

Sirenes, engraving from Symbolorum & emblematum by Joachim Camerarius, 1590-1605 (Image from Linda Hall Library);

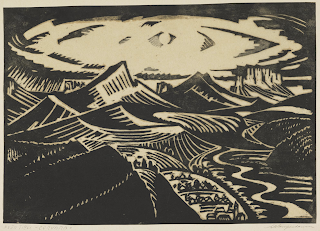

Proteus, wood block print from Emblematum libellus by Alciato, 1546 (Image from Glasgow University).]