Here’s a wintry poem, and an interesting bit of fantasy by Viola Meynall (UK, 1885-1965). It’s not so much a story as a scenario, a very simple “What if?” What makes it particularly interesting, though, is that it isn’t asking “What if the ocean froze over?” Rather, it’s asking, “What if the Ocean chose to freeze?” Indeed, it is actually freezing itself.

The sea would flow no longer,

It wearied after change,

It called its tides and breakers in,

From where they might range.

It sent an icy message

To every wave and rill;

They lagged, they paused, they stiffened,

They froze, and were still.

It summoned in its currents,

They reached not where they led;

It bound its foaming whirlpools.

“Not the old life,” it said,

“No fishes for the fisherman,

Not bold ships as before,

Not beating loud for ever

Upon the seashore,

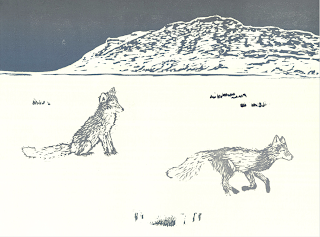

“But cold white foxes stepping

Onto my hard proud breast,

And a bird coming sweetly

And building a nest.

“My icebergs shall be mountains,

My silent fields of snow

Unmarked shall join the land’s snowfields —

Where, no man shall know.”

This ocean is personified - but not too personified. It is given consciousness, will, and abilities such as communication, but it is definitely not human. It seems not only tired of being in constant motion, but almost rebellious: no fish for you! (I can certainly imagine the ocean having had enough of humans on it, although our poor oceans are warming up instead of freezing.) Some of the images are really lovely, such as, “It summoned in its currents,” and “cold white foxes stepping onto my hard, proud breast.” By the end Earth is really an alien planet, with its solid ice surface above liquid seas below, like some of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. I certainly wouldn’t want to experience a cataclysm like the freezing of the ocean (would the foxes and birds survive, either?), but it makes a great poem!

[Pictures: Sea Ice, color woodblock print by Ina Timling (Image from Etsy shop TimlingPrints);

The Sinking of the Jeannette, wood engraving by G.T. Andrew after a design by M.J. Burns, 1884 (Image from Naval History and Heritage Command);

Arctic Fox and Slope Mountain, woodcut and linocut by Teal Francis, 2016 (Image from TealFrancis.com).]