Today’s post is dedicated primarily simply to quoting a cool excerpt from a book entitled The Discovery of a World in the Moone or A Discourse Tending to Prove that ’tis probable there may be another habitable World in that Planet, by John Wilkins, 1638. Wilkins (UK, 1614-1672) was a clergyman and a polymath, and one of the founders of the Royal Society academy of sciences. This was his first published work of popular science. The quotation below comes at the very end of the treatise, after he has carefully set up his logical arguments, step by step, through twelve preliminary propositions. (I leave the original spelling because I think it’s not too hard to understand.)

’Tis the method of providence not presently to shew us all, but to lead us along from the knowledge of one thing to another. ’Twas a great while ere the Planets were distinguished from the fixed Stars, and sometime after that ere the morning and evening starre were found to bee the same, and in greater space I doubt not but this also, and farre greater mysteries will bee discovered. In the first ages of the world the Islanders either thought themselves to be the onely dwellers upon the earth, or else if there were any other, yet they could not possibly conceive how they might have any commerce with them, being severed by the deepe and broad Sea, but the after-times found out the invention of ships, in which notwithstanding none but some bold daring men durst venture, there being few so resolute as to commit themselves unto the vaste Ocean, and yet now how easie a thing is this, even to a timorous & cowardly nature? So, perhaps, there may be some other meanes invented for a conveyance to the Moone, and though it may seeme a terrible and impossible thing ever to passe through the vaste spaces of the aire, yet no question there would bee some men who durst venture this as well as the other. True indeed, I cannot conceive any possible meanes for the like discovery of this conjecture, since there can bee no sailing to the Moone, unlesse that were true which the Poets doe but feigne, that shee made her bed in the Sea. We have not now any Drake or Columbus to undertake this voyage, or any Dædalus to invent a conveyance through the aire. However, I doubt not but that time who is still the father of new truths, and hath revealed unto us many things which our Ancestours were ignorant of, will also manifest to our posterity, that which wee now desire, but cannot know.

Many of Wilkins’s propositions are strictly logical (1. That the strangenesse of this opinion is no sufficient reason why it should be rejected.) and among the scientific assertions, some have turned out to be confirmed (4. That the Moone is a solid, compacted, opacous body. 5. That the Moone hath not any light of her owne.). Others turned out to be wrong (8. That the spots represent the Sea, and the brighter parts the Land. 10. That there is an Atmo-sphaera, or an orbe of grosse vaporous aire, immediately encompassing the body of the Moone.). But the really important thing is that Wilkins was not afraid to speculate, and to build his speculations on logic and the science of his day.

I really love both the argument itself, and the method of expressing it. I love that Wilkins admits his ignorance when appropriate, and maintains a calm and scientific basis for his speculation. And of course he was right that people would someday find a way to reach the moon, and wrong that they would find it inhabited. His logic, however, is still perfectly valid, and there’s no reason that it can’t still apply to other planets that seem as far beyond our reach as the Moon seemed to him.

If Wilkins had ever encountered creatures from another world, I feel sure that he would have been delighted to meet them, and tried his best to find common ground. In a period of great political and religious upheaval in England, Wilkins was noted for his ability to work with people from all camps, his insistence on religious and political tolerance in the church and the universities, and non-partisan inclusion in the Royal Society. He helped reduce tensions in both religious and academic circles, and seems to have been remarkably widely liked and respected. No doubt he would have worked hard to ensure that humans and aliens were on good working terms.

You can read the entire Discourse at Project Gutenberg.

[Pictures: title page of The Discovery of a World in the Moone, wood block and type, 1638 (Image from Internet Archive);

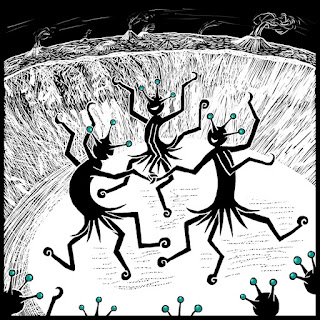

Ni is for nickel, illustration by AEGN for Periodic Table of Alien Species by Miguel O. Mitchell, 2021.]