James Whitcomb Riley (USA, 1849-1916) was famous for his poetry written in Indiana dialect, much of it for children, often humorous or sentimental, and supposed to represent ordinary folks. He was especially famous in his lifetime for his live performances of his poems. This poem is based on a 12 year old orphan girl named Allie, who worked for Riley’s family when he was a young teen. He had written the poem in 1885 as “Little Orphant Allie,” but it was printed as “Annie” because of a typesetter’s mistake.

Little Orphant Annie’s come to our house to stay,

An’ wash the cups an’ saucers up, an’ brush the crumbs away,

An’ shoo the chickens off the porch, an’ dust the hearth, an’ sweep,

An’ make the fire, an’ bake the bread, an’ earn her board-an’-keep;

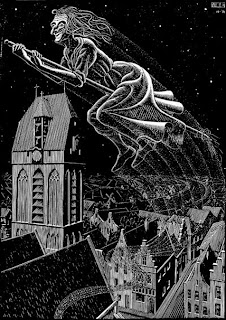

An’ all us other children, when the supper-things is done,

We set around the kitchen fire an’ has the mostest fun A-list’nin’ to the witch-tales ‘at Annie tells about,

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

Wunst they wuz a little boy wouldn’t say his prayers, —

An’ when he went to bed at night, away up-stairs,

His Mammy heerd him holler, an’ his Daddy heerd him bawl,

An’ when they turn’t the kivvers down, he wuzn’t there at all!

An’ they seeked him in the rafter-room, an’ cubby-hole, an’ press,

An’ seeked him up the chimbly-flue, an’ ever’-wheres, I guess;

But all they ever found wuz thist his pants an’ roundabout: —

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

An’ one time a little girl ‘ud allus laugh an’ grin,

An’ make fun of ever’ one, an’ all her blood-an’-kin;

An’ wunst, when they was “company,” an’ ole folks wuz there,

She mocked ’em an’ shocked ’em, an’ said she didn’t care!

An’ thist as she kicked her heels, an’ turn’t to run an’ hide,

They wuz two great big Black Things a-standin’ by her side,

An’ they snatched her through the ceilin’ ‘fore she knowed what she’s about!

An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

An’ little Orphant Annie says, when the blaze is blue,

An’ the lamp-wick sputters, an’ the wind goes woo-oo!

An’ you hear the crickets quit, an’ the moon is gray,

An’ the lightnin’-bugs in dew is all squenched away, —

You better mind yer parunts, an’ yer teachurs fond an’ dear,

An’ churish them ‘at loves you, an’ dry the orphant’s tear,

An’ he’p the pore an’ needy ones ‘at clusters all about,

Er the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you Ef you

Don’t

Watch

Out!

There are two points I want to mention regarding this poem and where it stands in the world of speculative fiction. First is the idea of telling scary stories - and having “the mostest fun” listening to them. From time immemorial people have gathered around campfires and in darkened rooms to amuse each other with the telling of horror tales. Intellectually I understand the idea of flirting with fear in a safe setting, but at a gut level I’ve never understood this at all; I just don’t find fear in any way enjoyable. I seem to be one of that small minority who simply doesn’t like being scared - but the rest of you can carry on and live it up this Hallowe’en!

The second spec fic staple this poem uses is the nursery bogey. Nursery bogeys are creatures used to scare children into good behavior and to warn members of a community of the dangers of breaking community mores. I’ve mentioned a number of nursery bogeys in past posts, including the Ninki Nanka and kelpie who will get you if you stray too close to dangerous waterways, and Krampus, who will punish you if you misbehave before Christmas. Little Orphant Annie tells of monsters that punish children who mock their elders or don’t say their prayers. Once again, this is not my favorite aspect of fantasy, but once again, humans seem to have been employing it since the dawn of language.

At any rate, Riley has had fun invoking the “enjoyable” kind of horror in this poem. You can actually hear him performing it here! Although since he was recorded on a phonograph record in 1912, it’s not very clear. (Further trivia that illustrates the popularity of the poem: the red-headed comic strip-cum-Broadway character (debuted in 1924) was named after Riley’s poem, although she doesn’t seem to have much in common beside the name. Neither does the also-red-headed Raggedy Ann doll, who in 1915 was named after a combination of two poems by Riley: “Little Orphant Annie” and “The Raggedy Man.”)

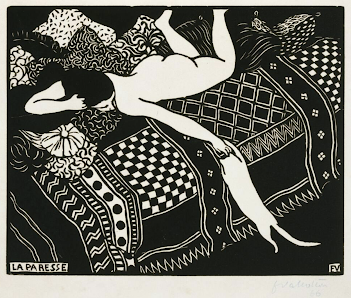

[Pictures: Little Orphan Annie, illustration by Ethel Franklin Betts, 1892 (Image from Project Gutenberg);

Film still from “Little Orphant Annie” directed by Colin Campbell, 1918 (Image from Wikimedia Commons).]

Moore.jpg)