The game of modern international chess was not standardized until the end of the nineteenth century, but of course its roots go back much farther - which has given it plenty of time to have a surprisingly large influence on the English language. Records of chess first appear in the seventh century, placing its origins in India, although the first depictions are from Persia, where it was called chatrang. In English, however, as well as many other European languages, the name for the game came ultimately from the Persian word for “king”: shah (passing through Old French and Vulgar Latin on the way).

By the Middle Ages chess was an important part of culture for the nobility, and ever since it’s been considered an indication of high intellect, judgement, and even moral allegory: foresight, caution, staying a step

ahead of one’s opponent… The cultural importance of chess turned it into a reference point that gave us lots of other words.

checkmate - from the Arabic phrase shah mat meaning “the king is dead” or possibly “the king is helpless”. This word is widely applied to any situation in which someone is stymied or thwarted. The verb check, “to bring something to a stop” (1620s) (think of checks and balances (1782), or of unchecked power) is simply a shortening of checkmate, and from there it just kept spreading to a whole host of other meanings, including…

• to hold up or control something, by verifying against an authority, ie to check a fact, to put a check mark on a list (by 1856), or to leave your belongings in the coat check (c 1812)

• check in or out of a hotel, or a book from a library (1909)

• check (out) - to investigate (from 1959)

• check-up - careful investigation (especially of health) (1921)

Then there’s the black and white pattern of the chessboard itself, giving us

• check (cheque) and checker - pattern of squares in alternating colors, as well as a fabric with that pattern, plus the checkered career of certain businessmen, for example

• exchequer - department of revenue, this name comes from the use of a checked cloth on which counters were used to reckon sums of money (from c 1300)

• check - the bill in a restaurant (1869), check - money order drawn on a bank (1798)

stalemate - when a chess player has no available moves. Somewhere along the line people added the “mate” of checkmate somewhat inaccurately to the original word stale, with the same meaning. (It’s related to stall “to delay, or to be stuck.”) pawn - the name of the chess piece comes ultimately from Latin pedonem meaning “foot soldier,” and eventually expanded to the metaphorical sense of a person who is powerless and manipulated in the schemes of others (1580s) (But it is unrelated to the meaning “something given as a security deposit.” Also, the chess piece rook does not seem to be related to the other meanings of rook in English.)

I was certainly surprised that all our various and seemingly boring, basic meanings of check derive from a game! Were you? As for me, I’ve never enjoyed playing chess; I don’t like my recreation to be that adversarial and stressful! But I do enjoy the aesthetics of the pieces… and of course I have to appreciate something that builds a whole world from simple black and white.

[Pictures: Chess board, wood block print from Repetición de amores y Arte de ajedrez by Luis De Lucena, c 1496 (Image from Biblioteca Virtual del Patrimonio Bibliográfico);

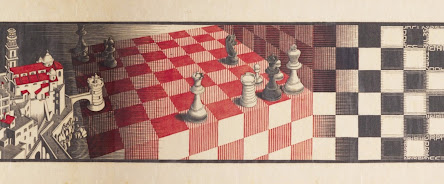

Detail from Metamorphosis II, woodcut by M.C. Escher, 1939-40 (image from Sotheby’s);

The Book of the Duchesse, wood engraving by William Harcourt Hooper after Edward Burne-Jones from the Kelmscott Chaucer, 1896 (Image from The British Museum);

Irrational Position, color woodcut by Elke Rehder, 2000 (Image from Art 3000);

Bandemor and the Lady, wood engraving by Samuel Williams from The Castle of Claimarais, 1830 (Image from The British Museum).]