I confess to enjoying the creative and varied idioms with which people insult each other’s intelligence. I find them humorous, and poetic, and interesting in what they tell us about the ways we think about intelligence and the workings of the human mind. There are a few metaphoric structures I particularly enjoy. The first of these is lacking. Some examples include

not playing with a full deck

not firing on all cylinders

one banana short of a bunch

two tomatoes short of a salad

a few clowns short of a circus

a few sandwiches short of a picnic

a few bricks shy of a load

a few French fries short of a Happy Meal

12 shy of a dozen

3 cents short of a dollar

his/her puzzle is missing some pieces

a few episodes short of a full season

The basic metaphor here is that a fully-functioning brain is like a complete X, so when a person isn’t thinking too well, it’s like having an incomplete X. What I enjoy about this is the wide range of things that can serve in the metaphor. “Not firing on all cylinders” is pretty straightforward, because imagining the brain to be like an engine seems reasonable, and everyone knows that a malfunctioning engine is a problem. But what about people who don’t even like tomatoes in their salad? And is a circus really a good metaphor for a fully-functioning brain?

The second metaphoric structure is intelligent objects. Of course, the objects themselves are not intelligent; rather, they stand in for intelligence because they’re characterized by traits that we use as metaphors for intelligence.

not the brightest bulb

not the sharpest knife in the drawer

not the quickest bunny in the meadow

not the sharpest tool in the shed

The basic traits that serve as metaphors for intelligence seem to be brightness/luminosity, sharpness, and swiftness/speed. Indeed, all of these words (bright, sharp, swift) are simple synonyms for "smart." So this group of idioms all use the structure of saying that someone does not have as much of the trait X as some object well-known for the trait X.

The third category is a bit of a catch-all, but one common theme these all share is the metaphor of the mind as a building.

the elevator doesn’t go all the way to the top

the lights are on, but no one’s home

a few tiles loose

bats in the belfry

All of these work because an unsound or inadequately-functioning structure represents an unsound or inadequately-functioning brain. (The last two are more often idioms for insanity than unintelligence, but I included them because there is a bit of overlap, and they fit with the same points I’m making with the others.)

All of these idioms illustrate some interesting things about us humans. For one thing, they show that we are not always very kind to each other, and for another, that we’re not always very tolerant of those whom we deem to be not mentally “normal.” But on the other hand, they also demonstrate our incredible creativity, and how much we value intelligence, as well as the way we love to play with language. These phrases reveal some of the metaphors for how we think about thinking, and how we try to get a grip on our own mysterious mental powers.

Now, I’m certainly not advocating that you use any of these phrases to hurt people’s feelings or make others feel bad, but as a linguistic game? Bring ‘em on! Have you ever heard any other idioms along these lines? Can you make up some new ones? What about idioms in other languages? I love to hear them all, though hopefully not used to describe me.

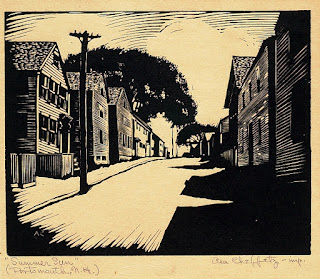

[Pictures: Banana Grove, linocut by Bruce Goold, 1992 (Image from Australian Galleries);

Hare, wood engraving from An Alphabet of Animals, 1865 (Image from Digital Archive);

British bats at home, wood engraving from Cassell’s Natural History, 1896 (Image from Project Gutenberg).]