The word divine, an adjective for God or gods, comes from Latin (by way of Old French), and ultimately from a Proto-Indo-European root meaning “to shine,” relating to the sky, heaven, and gods. Divine is far from the only English word with a god in its etymology, however. It’s clear to see how the diva on the stage is a goddess, deriving from the feminine of the same root. But other words are a little more unexpected. (Including one more from the divine root, here.) Hygiene comes to English in the 1670s from French, which got it from Greek. It comes from the goddess Hygieia, a daughter of Asclepius, the god of medicine. She was the goddess of health, cleanliness, and sanitation. One of her sisters was Panacea, goddess of universal remedy, whose name has also become an English word.

Going to the opposite end of the spectrum, let’s consider termagant, a word that doesn’t see a lot of use these days, but which means “a violent, overbearing person (most often of women)”. This word comes from the name of a god, but not one that anyone ever believed in. Teruagant (or other spellings) was a fictional Muslim god in medieval European literature, which didn’t have a clue about actual Islamic beliefs. The word shifted to become applied mostly to women apparently because the character of Termagant was depicted on stage wearing long robes like a gown, and since all actors were men anyway, the audience may have interpreted the character as being a female.

Another strong and offensive character is ammonia, a colorless gas with an overpowering smell. The word was coined in 1782 based on the older sal ammoniac, or “salt of Ammon.” Ammon was the Greek and Roman name for the Egyptian sun god Amun, in whose oracle temple visitors could collect the ammonium chloride crystals. Erotic comes directly from Eros, the Greek god of sexual love.

Iridescent, as well as iris (both the flower and the eye color), come from Iris, the messenger goddess of the Olympian gods.

The pharmacist who first isolated the opiate morphine named it after Morpheus, a Greek god of dreams.

Your nemesis against whom you inescapably struggle is named for Nemesis, the Greek goddess in charge of bringing retribution upon those who disrespect the gods.

A panic may be caused by Pan, the Greek god of the wild.

Your breakfast cereal derives from Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture.

As you can see, the Greek and Roman gods have given us no shortage of words!

Many people already know that the days of the week are named for gods: Tuesday for Tiw, an ancient Germanic supreme deity; Wednesday for Woden (aka Odin), the Germanic supreme god; Thursday for Thor, Germanic god of thunder (we could count the word thunder itself as deriving from the god, while we’re at it); Friday for Frigg (aka Frija), Germanic goddess of marriage, motherhood, and prophecy; and Saturday for Saturn, Roman god of time and father of Jupiter. And now it’s time to bid you adieu, the French salutation which literally means “to God,” short for “I commend you to God.” The Spanish version adios has also entered English. But did you know that our homegrown English goodbye is a contraction of “God be with you”?

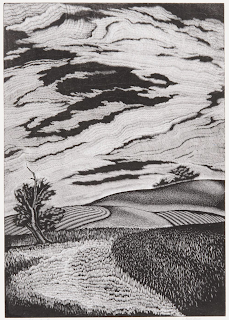

[Pictures: Hygieia, engraving by Raffaello Morghen, before 1833, representing an ivory bas-relief, c 400-430 CE (Image from Wellcome Collection);

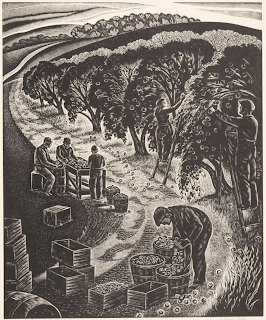

The oracle of Jupiter Ammon, engraving by Abraham Ortelius, 1624 (Image from Bibliotheque nationale de France);

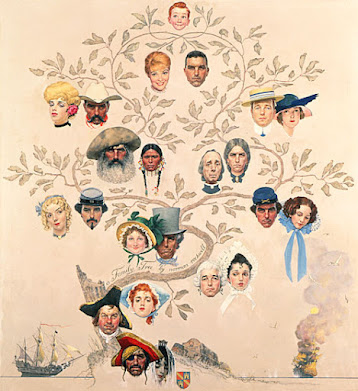

Frigga spinning the Clouds, illustration by J.C. Dollman from Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and Sagas by H.A. Guerber, c 1909 (Image from Internet Archive).]