Mexico has a long history of using art, including relief block printing, in politics and social activism. The Taller de Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphic Arts Workshop) is a Mexican collective of printmaking artists founded in 1937 and “primarily concerned with using art to advance revolutionary social causes.” It made mostly posters and handbills supporting certain political causes (and of course condemning others), but also made portfolio editions of some prints.

Wood block printing is still being heavily used by the ASARO collective (Assembly of Revolutionary Artists of Oaxaca) that was established with the conflict in Oaxaca that came to a head in 2006. It’s very cool that art (and especially relief block printing) is so vital and immediate in getting out messages. Its role is made even more important by the fact that multiple languages are spoken in Mexico, and in many regions there is no one language spoken by everyone. Go art, the universal language!

But I confess that for all the power of the best pieces made by Mexican political artists, I tend not to like much of their art. After a while it all begins to look the same: raised fists, evil soldiers, marching workers, banners, corpses… It begins to seem as if all those artists working for all those years could appeal to only one emotion: rage. There’s a place for anger of course - we need physical pain to tell us when something’s wrong with our bodies, and we need anger to tell us when something’s wrong with our societies. Nevertheless, a steady diet of rage quickly becomes unpleasant and eventually unhealthy. And if Mexico has a long history of relief printing, it has an even

longer history of using powerful art to make chilling statements about politics and power. Images of decapitated human heads and devoured human hearts are so prevalent in the art of the Mayan archaeological site Chichén Itzá that my children and I began to chant a little club beat ditty “Heads ’n’ hearts ’n’ heads ’n’ hearts…” at every new frieze. And that brings me to another point about political art: look at enough and it all looks the same regardless of which side it's supporting. Our side is martyred and their side must be crushed, always always always. Yes, we need the anger to tell us there’s a problem that needs fixing, but it seems to me that the rage is only the alarm call and not the solution. For the solution we need to let go of the bloodthirsty frenzy of heads ’n’ hearts ’n’ heads ’n hearts and actually use our heads and our hearts to reach real solutions.

[Pictures: Ayude a impedir este crimen (Ethel y Julio Rosenberg), linoleum block print by Francisco Mora, 1953;

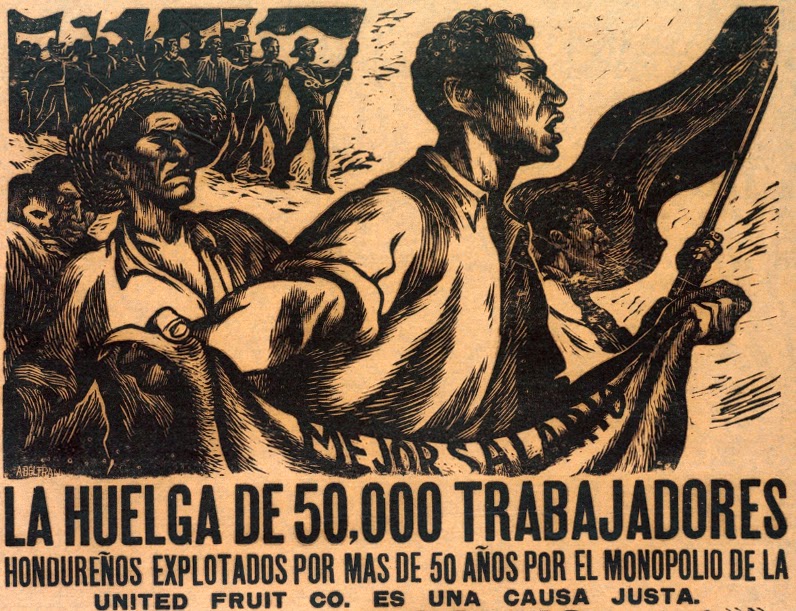

La Huelga de 50,000 Trabajadores, linleum block print by Alberto Beltrán, 1955 (Images from Princeton University Digital Library);

La Serpiente, wood engraving by Leopoldo Mendez, c 1943 (Image from Live Auctioneers);

Nuestros Muertos, wood block print by APPO Cooperative, 2006 (Image from Illustration Concentration);

Stone carvings at the tzompantli in Chichén Itzá, c 1200 CE (Image from The Flying Kiwi since I didn’t want to bother scanning my photo!).]

2 comments:

You might not understand the rage if you’ve never experienced persecution. How else do you express your despair of lost loved ones in the face of an authoritarian government?

Hello, Anna. Thanks for the comment. It’s a very valid point and I agree that these are incredibly eloquent and powerful expressions of a rage that is absolutely understandable. It’s amazing to see how these artists have given a voice to the unspeakable, and there is definitely a vital role for that. I don't deny the necessity of rage, or its power, but I do feel that ultimately there is a limit to how much healing rage can provide without other emotions and ways of reacting and acting, as well.

Post a Comment