It’s New Year’s Eve and tonight at midnight millions of people around the world will be raising a glass of something involving alcohol, and toasting stuff. So let’s take a closer linguistic look at where this all comes from…

First, the alcohol itself - Our word comes from Arabic al-kuhl, which means “the kohl.” Yes, we’re talking about antimony sulfide in a very fine powder form used as makeup, especially eye-liner, alá Cleopatra. When the word first entered English in the sixteenth century it meant “powdered cosmetic.” However, this fine powder was made by sublimation, or essentially distillation, which meant that soon other things made by distillation, including liquids, came to share the name. “Alcohol of wine” was the intoxicating ingredient in that beverage, and not until the mid eighteenth century did plain “alcohol” refer to this. (A hundred years later the word’s meaning was expanded back out to include the entire class of chemical compounds.)

The most popular drink at the New Year is probably Champagne, which of course is named for the region in France whence it originates, but some might choose other poisons (after all, intoxicate means quite simply “to poison” from Latin). Some possibilities include

rum - short for rumbullion and rombostion, though where either of those words came from is unclear. They’re possibly related to the adjective rum originally meaning “good, valuable,” though by the end of the eighteenth century it had shifted to its modern sense of “strange, bad, spurious” perhaps because of how dubious were the people and things to which the slang rum was so often applied.

gin - short for geneva, which has nothing to do with the Swiss city, but rather with the Dutch word for juniper, with which berries the drink is flavored.

whisky/whiskey - from Irish uisge beatha “water of life.” This is on an analogy with Latin aqua vitae (from which also French eau de vie for brandy.)

hooch - short for Hoochinoo, from the name of a native Alaskan tribe whose liquor was popular with miners in the Klondike during the gold rush. (The tribe’s name, from Tlingit Hutsnuwu, is supposed to mean “grizzly bear fort.”)

But whatever booze you pick (booze was originally a verb meaning “to drink a lot” but was helped along linguistically by a nineteenth century Philadelphia distiller named Edmund G. Booz.) chances are you’ll make a toast, so called because of the actual slices of toast the Romans put in their communal cups of wine. Then call out: Cheers (British)

Prosit (German, from Latin “may it be good for you”)

Skoal (Danish, literally “bowl, cup”)

Salud (Spanish, “health”)

Sláinte (Irish “to your health”)

L’chaim (Hebrew “to life”)

Chin chin (European, onomatopoeic for the clinking of glasses)

Here’s looking at you, kid (famous from “Casablanca”)

Personally, although I’m happy to join in toasts, I won’t be drinking any alcohol because I’m a teetotaller. This word was coined in 1833 by English abstinence campaigner Richard Turner. The word has nothing to do with tea (although I certainly do prefer tea to alcohol!). Rather it’s a stutter for emphasis. I’d probably have spelled it

t-total. Apparently tee-totally was a common slang adverb in some areas with an Irish dialect influence, including parts of North America, but Turner seems to have been the one to apply it to t-total abstinence. At any rate, so determined was he to claim credit that he actually has “Author of the Word TEETOTAL” carved on his gravestone.

But whatever you drink tonight, be it water, whisky, ginger ale, gin, or tea, I wish you a healthy and happy new year!

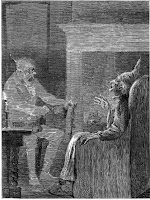

[Pictures: Men raising a toast, woodcut from Every Body’s Toast Book, and Convivial Companion “by an Adept,” 1851 (Image from The Butcher’s Floor);

Still Life II, rubber block print by AEGN, 2009 (sold out).]