Written by John Keats in 1819, this is one of the most famous, most referenced fantasy poems to come out of the Romantic movement. (There are two versions, by the way. I give you here the original.) It is written in ballad form, and uses a question and response format to set the scene and then allow the knight to tell his tragic tale.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thy brow,

With anguish moist and fever-dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna-dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

‘I love thee true’.

She took me to her Elfin grot,

And there she wept and sighed full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lullèd me asleep,

And there I dreamed—Ah! woe betide!—

The latest dream I ever dreamt

On the cold hill side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Thee hath in thrall!’

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gapèd wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

The plot is pretty straightforward: the noble knight is destroyed by the femme fatale. (A little more background depth is added by the biographical note that at the time of writing this poem, Keats was himself madly in love. It was requited by the lady, but he was by then dying of tuberculosis.) Keats took the phrase “la belle dame sans merci” from a fifteenth century French poem in the courtly love genre, and for those who don’t know the French, it means “the beautiful woman without mercy.”

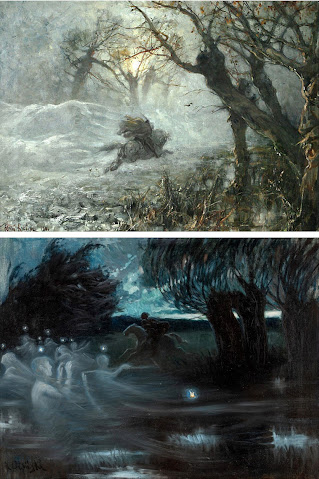

As I mentioned, this poem gets quoted and alluded to a lot, and needless to say, artists have loved portraying it. Mostly it seems to be an excuse to show a beautiful woman, with relatively little emphasis on the subsequent misery of the knight. Feel free to do a search for all the paintings on the theme, too.

From a feminist point of view, there’s plenty we could say about the trope of the belle dame sans merci: the demonization of any woman deemed too promiscuous, and the simultaneous demonization of any woman who refuses the advances of the man telling the story. But I’m here to look at things from the fantasy point of view, and I find this poem interesting as a portrayal of fairy. This fairy is not cute and sparkly and good. Keats is describing a being that is very non-human: beautiful, seductive, addictive, strange, other… One could debate whether she is actively cruel or merely utterly amoral, but certainly she does not care what becomes of all the humans with whom she has dallied. She belongs to the tradition in which fairies are creatures without souls. This is the version of fairies that I am working with in my current work in progress, by the way, and this poem is one that I’m quoting in chapter headings.

[Pictures: Illustration by R. Gardner from

Lamia, La Belle Dame Sans Merci, & c by John Keats, 1900(?) (Image from

MrMorodo);

A Woman Embracing a Man (for

La Belle Dame Sans Merci), wood engraving by Michael Renton, 1986 (Image from

Roe + Moore);

Illustration by Lancelot Speed from

The Blue Poetry Book, 1891 (Image from

Project Gutenberg);

Illustration by Robert Anning Bell from

Poems by John Keats, 1897 (Image from

Internet Archive).]