It’s been a while since I mentioned Proto-Indo-European, so here’s a quick refresher: it’s an ancient language that no longer exists, but which linguists can extensively reconstruct by tracing back from all the known languages which descended from it, which include most of the languages of Europe and India including Latin and Romance languages, Celtic languages, Germanic languages, Greek, Slavic languages, Persian, Sanskrit and the Indian languages descended from Sanskrit. That’s a lot! It also means that many Proto-Indo-European (PIE) roots have produced a whole plethora of modern English words, by coming down through various branches and twisting and turning in various ways over the approximately 5000 years since PIE was spoken as a single unified language. I’m bringing it up today because I’m going to share just a few of the many English words that ultimately derive from the PIE root *kaput-. (The asterisk, by the way, indicates that the form is reconstructed, as opposed to directly attested, since there was no writing to directly attest any part of PIE.) *kaput- means head.

Let’s start right off by tackling the obvious question: is this related to the English word kaput? The answer is yes, but in a very indirect and convoluted way, so let’s take it step by step. English borrowed kaput from German (around 1895, but popularized during World War I). It means “destroyed, ruined,” but derived from a term that German had borrowed from French, faire capot, which referred to winning all the tricks in the card game piquet, which was popular in the 16th century. That French phrase literally means “to make a bonnet/hood,” but was also marine jargon for a sailboat being overset in a squall - or capsized. The capot which meant “bonnet or hood” in the phrase was also the name of a hooded cloak or cape (the word is, in fact, a diminutive of cape) worn by sailors and soldiers. The capes in question are named for their hoods or caps, which come from Latin caput “head” because of course they’re worn on the head. And the connection of Latin caput from PIE *kaput- is perfectly clear.

From cap and cape we also have all kinds of English words from hubcaps and cap-guns, to the chapel that I discussed previously. Then there’s escape, which literally meant “to get out of one’s cape,” presumably leaving it behind in the hands of the captor. (Captor, however, is unrelated, despite appearances.)

Other English words that derive from the Latin caput include biceps (c 1640, “two-headed,” because of the structure of the muscle), cadet (c 1610, from Gascon capdet, from Medieval Latin capitellum, a diminutive of caput), cad (c 1730, shortened slang of cadet), cape “promontory of land” ie “headland.” And don’t forget captain.

I need a whole paragraph just for capital in all its various meanings, but many of them involve a conflation of head with the meaning first. “Head city,” “top of a column,” and “upper-case letter” are pretty straightforward. Capital meaning “wealth” came from a distinction made in medieval Latin between the head or first sum of money and the subsequent interest added to it for a loan. Medieval Latin capitalis meaning “property” also led, by way of two dialects of Old French, to both cattle, which originally meant property of any kind, and chattel. Meanwhile, capital punishment involves a connection between the head and life itself, and of course sometimes meant decapitation.

Chapter is a division of a book or other organization - a heading, in fact. It’s another diminutive, and comes by way of Old French, which is where we also get the ch in the words chief, chieftain, kerchief (a cloth covering the head) and mischief (an event that comes to a head in a bad way), which is the opposite of achieve (literally “to come to a head”). On the other hand chef, despite its ch, is from modern French (1842). Capitulate comes from the idea of drawing up the terms of surrender in articles or chapters, but comes straight from Medieval Latin instead of going by way of French, and recapitulate means to go back over the main chapters or headings of discourse.

Then there’s precipice, literally meaning “before or forth + head,” in other words, “headlong or headfirst,” which is how you might fall down it. The verb precipitate came first by nearly a century, and precipitation was even earlier (late 15th century, of fallen angels and alchemical solutions - but rain didn’t fall into English with this word until the late 17th century).

You can also revisit cappuccino and cabbage, discussed last month, and add the uncut gemstone cabochon which comes from the same Old French slang as cabbage.

All the examples I’ve listed so far came into English by way of the Latin branch of PIE. But English also gets the version that developed directly down through the Germanic branch, which is where we get head itself. And of course head leads to a whole array of figurative uses, many of which we’ve already seen in the same ways the Latin version was used: top, first, most important, most prominent, individual, and so forth.

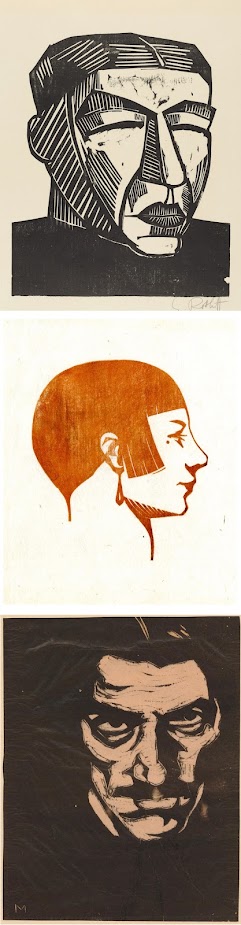

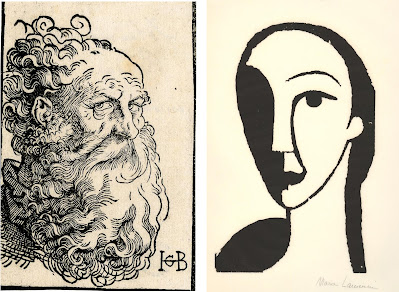

Whew, that’s a lot of heads for one day, illustrated with a lot of wood block prints of heads, so that’s enough from me before we all lose our heads!

[Pictures: Head of an Awa Doll, colour woodblock print by Taniguchi Kunbi, 1948 (Image from The British Museum);

Portrait head, woodcut by Wiktoria Goryńska, 1931 (Image from The British Museum);

Head of a mountain peasant, woodcut by Władysław Skoczylas, 1927 (Image from The British Museum);

Mother, woodcut by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, 1916 (Image from MoMA);

Tête, woodcut by Emile Charles Carlègle, 1932 (Image from The British Museum);

Self-portrait, woodcut by Emilio Mantelli, c 1911-18 (Image from The British Museum);

Head of an old man, woodcut by Hans Baldung, c 1518 (Image from The British Museum);

Grand tête de femme, woodcut by Marie Laurencin, 1910 (Image from The British Museum).]

No comments:

Post a Comment