Perhaps you say “tom-ay-to” and I say “tom-ah-to,” but we both agree that we are, in fact, saying the same word despite different pronunciations. Obviously this is the case with

the vast majority of words in any given language - that speakers recognize different dialect pronunciations as being the same word. However, English does have a handful of exceptions. These word pairs are actually simply two different pronunciations of the same word, which somehow came to be reinterpreted and accepted as being separate words.

the vast majority of words in any given language - that speakers recognize different dialect pronunciations as being the same word. However, English does have a handful of exceptions. These word pairs are actually simply two different pronunciations of the same word, which somehow came to be reinterpreted and accepted as being separate words.

girl, gal - Two words with similar meanings, girl has been around since about 1300, while gal was an eighteenth century pronunciation noted in New England. It’s similar to the Northern English dialect usually indicated gell or gel, but somewhere along the line gal gained its own identity as a separate word, rather than simply a phonetic spelling of a dialect pronunciation.

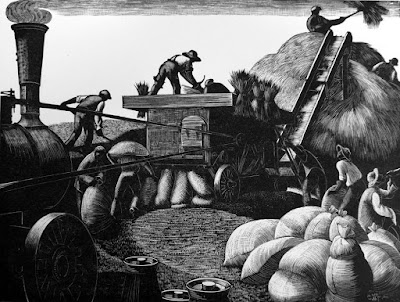

thresh, thrash - Thresh is an Old English word meaning to sift grain by beating it. Thrash is recorded as a dialectal variant of thresh from the 1580s, but had gained its own slight twist, “to beat [something other than grain],” around 1620. I can only guess that if the meaning shift first occurred in an area with a slightly different pronunciation, it was that area’s pronunciation that was attached to that new meaning.

vermin, varmint - Most people probably think of critter and varmint as slangier or dialectal words, the sorts of things Yosemite Sam hollers, and not the sorts of words you would use in serious writing. They probably became their own words precisely because they struck people as funny, and distinctively indicative of a certain sort of hillbilly or Wild West speech. They are both Americanisms from the early nineteenth century, although the spelling “varment” was found in dialect areas of Britain in the 1530s. One interesting note, though, is that there are many words in which modern Standard North American dialect pronounces er while British Received pronunciation says ar: clerk, Derbyshire, shard/sherd, and so on. So varmint and critter are probably fairly accurate indicators of the original pronunciation of English colonists.

saucy, sassy - Sassy is simply an American version - I’m pretty sure a southern American version - of saucy. Saucy meaning “cheeky” dates from the 1520s, while sassy dates to the 1830s. Really, they mean exactly the same thing, and I can’t tell you why sassy now gets its own spelling and entry in the dictionary, but I’m glad it exists as its own word. It gives all of us the option to use either pronunciation whatever our own dialect may be.

hoist, heist - Here’s a set where our different pronunciations have acquired quite different meanings. The original, hoist, had various slang meanings among criminals: “to steal” (note similar meaning in shoplift), or “to lift up an accomplice to reach a window to break in.” It’s the American pronunciation that, in the 1930s and 40s, took those slang meanings and gave them a word of their own. (By the way, the noun, meaning “a robbery,” came first.)

roil, rile - Perhaps you recognize the sound pair here, even though it’s spelled differently from the one above: oi - i. Once again roil, “to stir up or muddy,” is the original word, while rile is the phonetic spelling of the American pronunciation. (In 1848 John Russell Bartlett wrote that rile was a common pronunciation and spelling in both Britain and America, but I’m assuming only as a dialectal variant in Britain.) Once again the slightly shifted sense, “to agitate [people],” became attached to the variant pronunciation, leaving the original pronunciation with its original meaning.

strop, strap - Everyone knows the word strap, while strop is somewhat more obscure. It’s the leather band on which to sharpen razors. Nevertheless, it’s strop that’s the original word for a band of leather, while strap is a Scottish and possibly nautical pronunciation. Why did the dialectal version completely displace the original some time in the sixteenth century? I can’t tell you. (And in case you’re wondering, strip is not closely related to either, despite ending up with a similar sound and meaning.)

stamp, stomp - You might think that stomp and stamp would follow the same pattern as strop and strap. If you thought that you’d be displaying good linguistic instincts - but you’d be wrong. This time stamp is the older Old English word, with the meaning “strike the foot forcibly downwards” from the mid-fourteenth century. It’s stomp that’s the variant, from about 1800. Unfortunately, I don’t know what dialect is responsible for giving us stomp.

Why do some dialect pronunciations get to be spelled phonetically and become their own words, while most don’t? Why do some even get to add their own unique definitions to the language while others remain synonyms of the original? I don’t think anyone can explain it, but it is a fun phenomenon.

[Pictures: Threshing, wood engraving by Clare Leighton, c 1933 (Image from Warwick Leadlay Gallery);

Yosemite Sam, drawings by Warner Bros. Animation studio;

Razor strops, wood block prints from Montgomery Ward Catalog, 1895 (Image from Kristin Holt).]

No comments:

Post a Comment