I previously did a post about Saint George slaying the Dragon, which you should go ahead and see here: St George’s Day. In it I have a wide variety of wood block prints of the scene, ranging from around 1504 to 1941. But in the more than ten years since that post, I’ve collected a bunch more prints on the theme, so here’s another collection.

Knights killing dragons has long been a very popular theme for artists, with Saint George being the most popular one of all. The iconography tends to be fairly standardized: George is most often riding a horse and plunging his lance down the throat of the dragon on the ground below. Often the damsel in distress is shown in the background. Sometimes you can see George’s shield or pennant with his cross on it, although of course in most wood block prints it’s black-and-white instead of red.

Today’s first three examples are all very standard, but they have some interesting details. Number one, by Albrecht Dürer, has the princess peering out from behind a boulder, plus some bones scattered around the ground to demonstrate just how dangerous the dragon is. I love its feet and long tail corkscrewing away into the distance. The dragons are often quite small, as in today’s second piece, but Dürer’s dragon is as large as the horse, which is quite respectable. As for the second piece, it shows the princess safely away on a clifftop, praying for the knight’s victory, but the most interesting thing about this one is the background. Wood block prints of this era seldom have dark backgrounds, but this one does a great job using the characteristics of relief printing for a nicely speckled dark ground and a patterned background that is reminiscent of the the patterns in hand-painted illuminations. These first two are both from the early sixteenth century, so you can see by the comparison why Dürer was considered such a master!

As for the third piece, it’s quite small and rough, with flaws in the image where the wood block presumably was cracked and damaged. The dragon, however, is kind of adorable, with wide, happy eyes and a big grin.

The next examples are also quite crude. Here are a series of three woodcuts from an eighteenth century chapbook, and they show three stages in Saint George’s battle: he rides up and greets the princess as the dragon rushes in from the left. The center is the standard iconography as George delivers the fatal thrust, and then the third image shows George having cut off the dragon’s head to bring back as a trophy. There’s a continuity error where his horse has changed color, and I think it would have looked better if it were black all along for a punch of contrast.

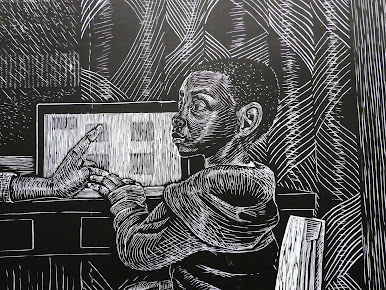

Next to those is a modern ikon in an interesting skritchy carving style. I like the saint’s halo and the glow of little lines making a sort of halo around the entire horse. The dragon is another funny one, but it’s got its tail around the horse’s leg so if it can survive just a few minutes longer it might bring George down!

The last two pieces today are the most dramatic of all. I particularly love the dragon in piece #6. He looks like he’s actually giving George a serious fight, having broken off the lance and spewing smoke. He’s got an interesting forked tail, as well. As for the knight, he doesn’t seem to be wearing armor or using a saddle, although he’s got quite the extravagantly plumed helmet. And the final piece puts a modern twist on the whole thing by mounting Saint George on a motorcycle. To balance that touch, the rest of the composition is very traditional, although carved in a rough expressionistic style. I love this twist on the traditional version.

As I said in my previous post on this topic, I’d rather see happy healthy dragons than glory in the violence of slaughter, but if I set aside my love of dragons and remember them as the representations of evil that they used to be, I’ll leave you once again with the quotation from G.K. Chesterton: Fairy Tales are more than true; not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.

[Pictures: Saint George, woodcut by Albrecht Dürer, 1504-5 (Image from The British Museum);

Saint George on horseback, wood block print by anonymous Italian artist, 1519 (Image from The Met);

Saint George of England, frontispiece of The most illustrious History of the Seven Champions of Christendome by Richard Johnson, 1661 (Image from Yale University Library);

Three woodcuts from “The Life and Death of St. George,” 18th c., from Chapbooks of the Eighteenth Century by John Ashton, 1882 (Images from Internet Archive);

Ikon, wood block print by Michael Aggelaki (Image from eikastikon);

Saint George and the Dragon, wood block print by Guiseppe Scolari, 1550-1600 (Image from Art Institute Chicago);

Victory. Saint George on motorcycle, woodcut by Igor Koutsenko, 21st c? (Image from Saatchi Art).]