Paranomasia, which is to say punning, depends on the fact that homonyms may cause lexical ambiguity, which is to say that similar-sounding words with different meanings can cause a sentence to be interpreted in more than one way. And although many people have sneered at puns as “the lowest form of humor” (Samuel Johnson) and despite their irritating popularity among five-year-olds, devising and decoding puns actually takes some really sophisticated brainpower. (Notice when young children try to tell knock-knock jokes before they actually have the brainpower to handle puns. Their attempts can often be funny, but only because of absurdity and adorableness, not paranomasia.) You have to interpret a single set of sounds in two markedly different ways, and hold both interpretations in your mind simultaneously, contrasting them. That’s what makes the joke funny: the difference between the expected meaning and the unexpected. Probably it’s precisely because puns require a high level of attention and verbal brain-work that knock-knock jokes use their invariable formula to warn you to get ready for some ludic language interpretation. Furthermore, many puns require knowledge of history or current events, cultural references, or complicated or specialized vocabulary. Knock-knock jokes in general, like much humor, can also serve sophisticated social functions, such as defusing tension, making something memorable, or marking solidarity.

The quintessential knock-knock joke begins with a name, as if a plausible person were at an actual door. When we follow the formula and respond as we might to a normal visitor, we’re given the punch line that requires us to reinterpret the information we’ve already received (the name) in an unexpected direction. (Admittedly, when the direction is wholly expected because this is the eight hundred sixty-seventh time our five-year-old comedian has repeated the same lines, it tends not to strike the funny-bone quite so forcibly.) Among my favorite punch-lines are

Dwayne who? Dwayne the bathtub! I’m dwowning!

Delores who? Delores my shepherd.

They work better the more complicated the name. There’s not much excitement to

Anne who? Another bad knock-knock joke.

After all, who can’t make up a sentence that begins with the sound an?

But Hiawatha who? You really wonder how that one’s going to turn into something else.

Then there are the ones that pun on the sound of “who” including

Boo who? I didn’t mean to make you cry.

Little old lady who? I didn’t know you could yodel.

I confess I find these less amusing, because they’re more predictable. As soon as “Boo who” has escaped your mouth you already know where this is going. Indeed you can usually see it coming as soon as the jokester says her bit. But much of the same brainwork is still going into them.

Once the form of the joke itself becomes universally known, then that’s another expectation that can be upended for comic effect. The one that was popular in my youth was

Banana who? Knock knock. Who’s there? Banana. Banana who? Knock knock… repeated until the jokester judged that the audience was on the verge of revolt. Then: orange.

Orange who? Orange you glad I didn’t say “banana?”

The one popular among the current generation of youth goes

Knock knock. Who’s there?

Interrupting cow. Interrup- MOOO!

Back in 1936, when the craze was at its height, columnist Heywood Hale Broun made up the following “joke”

Knock-knock. Who’s there? A gang of vigilantes armed with machine guns, leather straps and brass knuckles to thump the breath out of anybody who persists in playing this blame fool knock-knock game.

Personally, I think that seems a little harsh. Okay, so after all these knock-knock jokes maybe you’re laughing, maybe you’re groaning, and maybe you’re pursing your lips and wondering why you even bothered to read this far in a post about something so stupid. Even those who consider that “puns are the highest form of literature” (Alfred Hitchcock) have to admit that some are pretty darn bad. But even those who deplore and despise the humble knock-knock joke should acknowledge that the best require creativity, mental flexibility, principles of rhetoric, and elements of poetry. Language is one of the things that makes humans unique, and one of the uniquely wonderful things we humans do with language is play with it. Without wordplay language would lose its joy.

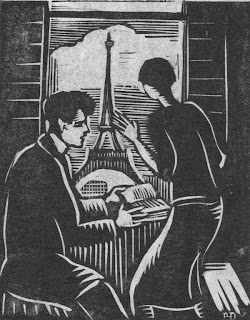

[Pictures: Rowell, rubber block print by AEGN, 2014;

Knocker from The Georgian Society: Records of Eighteenth-Century Domestic Architecture and Decoration in Dublin, 1909 (Image from AllPosters.com);

Decorative Hardware II, no info because (Image from art.com).]

(By the way, Hiawatha good girl until I met you. 1920’s idea of cute. Groan… but points for ambition.)