As everyone knows, English loves to borrow words from other languages. But we don’t just borrow any old word; the words we borrow give us all kinds of clues about our attitudes towards other languages and their speakers and cultures. What do we admire? What do we look down on? What do we consider different and foreign? What do we feel we need additional words to talk about properly? Today’s Words of the Month are a case study in borrowing: loan words from Italian into English.

We begin in the renaissance, when Italy was the banking center of Europe. English people may have borrowed money, but they certainly borrowed Italian words to get bank (late 15th c), bankrupt (1560s “broken bench”), and manage (“handle” 1560s).

When speakers of English under Elizabeth I were starting to feel good about their language after centuries of inferiority complex, both a cause and effect in the linguistic cycle that brought English to that point was the exuberant borrowing of words from all over Europe. From Italian we borrowed the words for what we admired most about Italian culture: art and architecture. (And remember that our friend Sebastiano Serlio was one of the Italian architects whose ideas were spread so widely and influentially, although Andrea Palladio is an even bigger name.)

cupola (1540s), motto (1580s, from heraldry), fresco and stucco (1590s)

portico (c1600), villa, grotto, and balcony (1610s)

With a touch of literature: novel (1560s), stanza (1580s)

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Italy had an enormous influence on the development of baroque and classical music, and English borrowed Italian musical terms wholesale.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Italy had an enormous influence on the development of baroque and classical music, and English borrowed Italian musical terms wholesale.

baritone (c 1600), opera (1640s), solo and sonata (1690s)

violoncello (shortened to cello in 1857), finale, trombone, tempo, oboe (a word Italian had borrowed from French hautbois) (all first appeared in English in A Short Explication of Such Foreign Words as are Made Use of in the Musick Books, 1724)

concerto (1730), soprano (1738), aria (1742), adagio (c1746), bravo (1761), pianoforte (1767), falsetto (1774), crescendo (1776)

Not all borrowings are for things we admire, however. English also borrowed bandit (1590s), stiletto (1610), vendetta (1846), and Mafia (1875) from Italian. Why borrow words for crimes when speakers of English could just as easily have spoken of thieves, daggers, vengeance, and organized crime in native English words? Sometimes it puts a romantic spin on a criminal, if a bandit seems more exotic and dashing than a footpad. But in many cases, by borrowing words for crime or other undesirable elements of culture, speakers put themselves at a distance. These are Italian criminals and Italian crimes, not good, wholesome English behavior. Vendetta and Mafia entered English with the waves of immigrants entering the United States during the Ellis Island period, and remind us of some of the stereotypes English speakers held about Italian immigrants.

The one area where languages almost always end up borrowing from one another is food, and through the centuries English has adopted many Italian food words along with the foods themselves.

artichoke (1530s), macaroni (1590s), broccoli (1690s)

And through the late nineteenth into early twentieth century waves of immigration:

lasagna (1846), salami (1852), pasta (1874), spaghetti (1885-90),

mozzarella (1911), zucchini (1915), pepperoni (1919), pizza (1935), pesto (1937)

Finally, here are a few bonus Italian words with interesting histories

umbrella (c1600, first used in English by John Donne)

vista (1650s)

casino (1744, but gambling house 1820)

graffiti (1851, from Pompeii)

lagoon (1670s, of Venice)

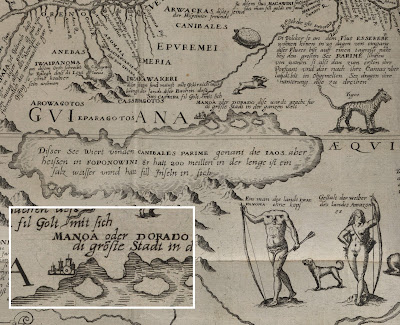

[Pictures: Portico and cupola on Chiesa di Santa Maria al Giglia a Montevarchi, wood block print from La Cento Citta d’Italia illustrate, 1896 (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

The Concerto, linocut (four blocks) by Cyril Powers c.1935 (Image uploaded by user on Pinterest);

Pasta, linocut by Haley Polinsky (Image from Etsy shop HaleyPolinsky).]