|

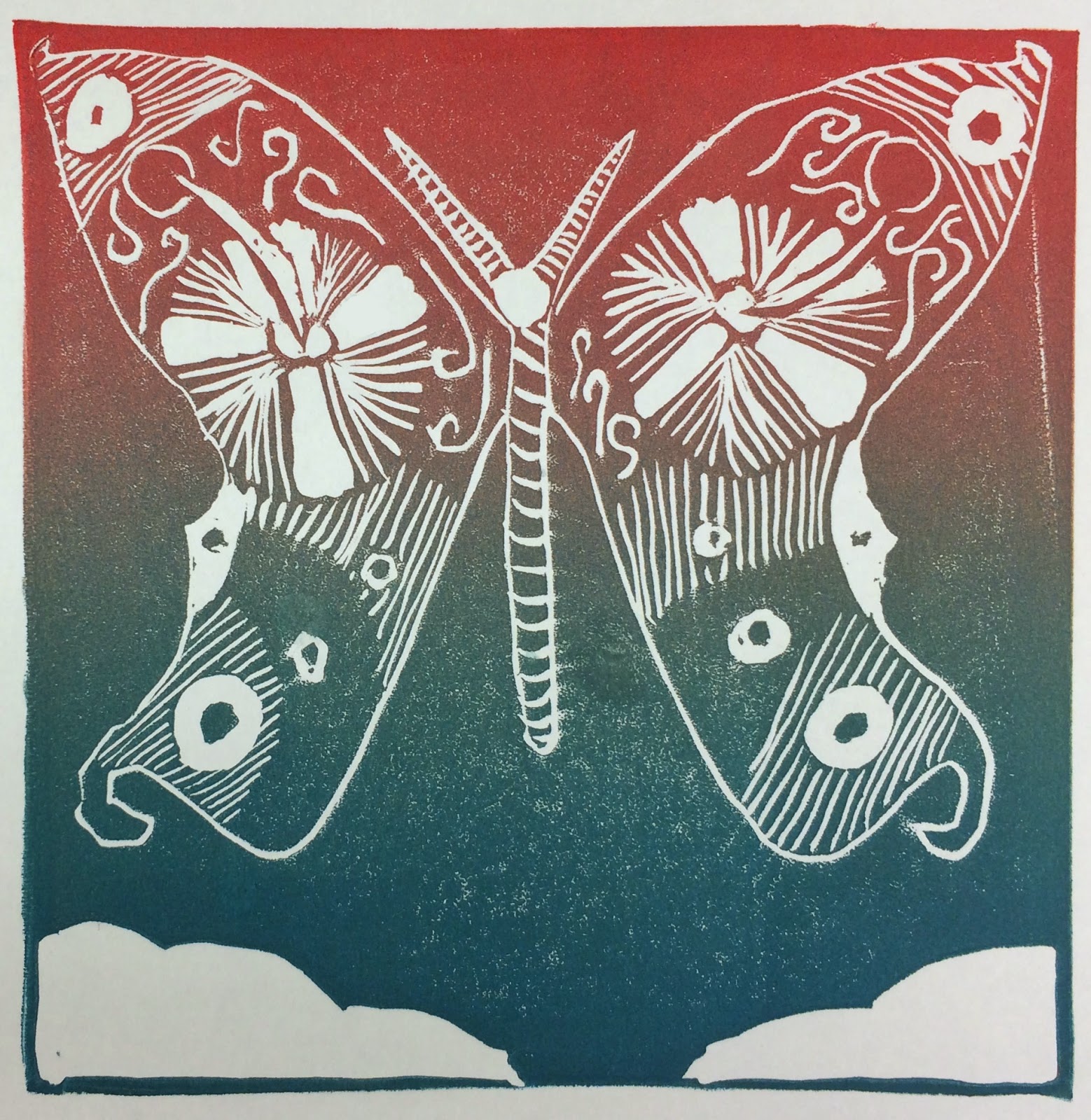

| How many distinct colors do you see in this print? What words would you call those colors? |

A second point to be made here is that just because a language may have only two “basic color terms” doesn’t mean that speakers of those languages can’t talk about subtle color variations. Of course they can; they just use adjectives, similes, and such: “dark like the color of a leaf in shadow” or “light as a cherry blossom,” for example.

English is a language unusually rich in words for colors. We have eleven out of twelve possible basic color terms. The only distinction we’re missing is separate words for light blue and dark blue (although we have separate words for pink and red - more on this in a later post!) But in addition to our basic color terms (black, white, red, green, yellow, blue, brown, orange, pink, purple/violet, and grey) we have a seemingly infinite array of non-basic terms. First of all, there are all the words that are simply based on an object of a particular color, such as ruby, rose, lavender, alabaster, silver, and chocolate. There are also compound words that add modification to our basic words, such as grass-green, blood-red, lily-white, sky-blue, and pitch-black, and those simile phrases such as white as snow and red as a lobster. But there are also an amazingly large number of words that are very specifically color words and nothing else, but which aren’t basic color terms because English speakers perceive them to indicate variants of more basic colors. Examples of these words include dun, beige, ecru, taupe, rufous, scarlet, crimson, maroon, puce, verdant, azure, cerulean, and magenta.

Many of these latter category of words began as similes, but are now color words pure and simple. Maroon, for example, comes from French for chestnut (1791), taupe comes from French for mole (early 20th century), scarlet comes from a kind of rich fabric (color meaning from late 14th century), and puce comes from French for flea (1787. Yeah, think about the implications of that: people were so familiar with the purplish-brown color of a flea that if you described something as “flea” everyone knew exactly what color you meant!) In fact even some of our basic color terms were once metaphorical, including pink and violet. As for orange, it was only in the twentieth century that it joined the ranks of red and yellow as a basic color term. It was used to describe color as early as the 1540s, but was seen as descriptive rather than basic for centuries, along the lines of peach or emerald.

So why do some languages have so many more dedicated color words than others? Why does English have so many wonderful words for colors? That’s a mystery and I don’t have an answer. I do know that, as usual, I revel in our rich rainbow of vocabulary. (And I know that there are more posts to come, dealing with additional interesting intricacies of color words. So tune in next month for more colorful Words of the Month!)

[Picture: Butterfly (Rainbow version), rubber block print by TPN, 2014.]