(This is it: we’ve reached the end of the alphabet! But you can still check out all the other A to Z Bloggers here. My A to Z Challenge theme this year is How to Make a Fantastical Creature, in which I explore 26 traits that are widely shared among the monsters and marvels of fantasy and folklore.)

Although many magical creatures have their birth in our nightmares, and others evolve with our solemn mythological, theological, and philosophical beliefs, some strange and magical creatures are really just for fun. Today I’ve got some of the silliest, zaniest beasties for you to enjoy. (Plus a whole lot of links to prior posts, since I do tend to like to feature zany critters!)

One whole class of zany monsters is called Fearsome Critters, and these are found in tales told by the lumberjacks and outdoorsmen of the American wilderness around the turn of the 19-20th century. They often have their origins as jokes and hoaxes. The jackalope is one of the more famous, and we encountered the hidebehind way back at A.

The wapaloosie was featured in my bestiary, and it hails from the damp forests of the Pacific Northwest, where its inchworm physique, zygodactyl claws, and spike-tipped tail allow it to climb the tallest trees with ease. It has soft, rich fur, but don’t bother trying to make mittens or coats or anything from it, because even when removed from the critter, the fur will compulsively continue to climb as high as it can into any tree nearby. Oops, there goes another pair of mittens!

Then there’s the whirling whimpus of Tennessee, which looks a bit like a gorilla with tiny feet and huge, heavy hands. It stands at a bend in a forest trail and spins so quickly that it becomes invisible (flashback to I). If a hiker should walk into its orbit, they will be pureed by the whirling hands. The only way to avoid this is to listen for the sound of a whirling whimpus whirling: a strange droning noise.

The tripodero inhabits brush around construction and engineering sites. Its two telescopic legs, balanced by a tail like a kangaroo, allow it to raise and lower itself in the scrub. When it sights prey, it aims, and blows a ball of sun-dried clay (which it stores in its left cheek pouch) through its snout with the force of a bullet.

The roperite from the foothills of the Sierras can run extremely fast so that nothing can outrun it, and its most distinctive feature is its strangely elongated and flexible beak, which it uses like a lasso to rope its prey.

These sorts of zany creatures abound in other places around the world, as well. The fur-bearing trout is a Fearsome Critter, but very similar furred fish inhabit the lakes and rivers of Scandinavia. In Australia can be found the vain and silly oozlum bird, and throughout Europe there are a variety of strange bird-rabbit-type hybrids, including the wolpertinger, the skvader, and the dilldapp. You can find out more about them (and others) here.

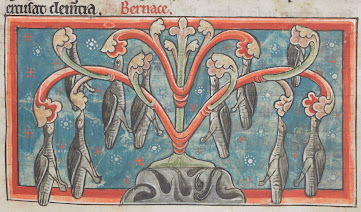

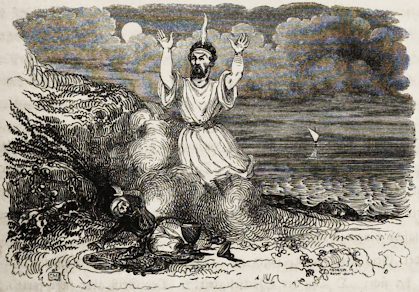

I can’t help suspecting that the bonnacon, which we met at B, was medieval comic relief, setting the monks to sniggering in their scriptoria. But of course those illuminators also indulged in all manner of unnamed marginal monsters that were as zany as it gets. We saw a few grylluses at X, and a funny winged thing at F, and here are a few more. There are no stories about marginalia, so we can only speculate about their life cycles, dispositions, and possible magical traits.

The hippogryph (mentioned at C and F) was originally introduced to the world as a zany creature, since it is the offspring of a griffin and a horse, two species that were considered to be utterly opposed and thus impossible to combine. There are also some

The welwa from a Romanian fairy tale is also pretty bizarre.

During the Edo period when there was a great craze in Japan for collections of yōkai (strange supernatural creatures and spirits), a number were made up for sheer entertainment. However, one of the yōkai I find particularly zany may not have been intended as a joke. The kamikiri is a sort of insectoid critter with razor teeth and scissor-hands, with which it sneaks up behind people and cuts off locks of hair.

In the western mountains of China you might encounter the dijiang (aka hundun), a very strange headless, faceless creature with six legs and four wings. Despite its odd anatomy, this critter can dance and sing. Recently it got its chance to star in a major motion picture, being featured in the 2021 Marvel movie “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” under the name of Morris.

Many modern fantasy authors have indulged their zany sides with strange creatures from Lewis Carroll’s toves, borogoves, and jubjub bird, to Douglas Adams’s mattresses and ravenous bugblatter beast of Traal, and Terry Pratchett’s definitely zany take on dragons.

Dr. Seuss offered entire books of zany beasts, of which I have previously mentioned the spotted atrocious and the foon (introduced at E), and will add today the yop which likes to hop (and is small enough it could have been featured at P).

Gustave Verbeek and Jack Prelutsky revelled in mythical mashups such as porcupineapples and umbrellaphants, to which class one of my own contributions is the capybureau. You can also learn about my discovery of the musical critters double-belled euphonibun, calliopine, harp-finned walkingcod, and more.

And check out another prior post to revisit such modern discoveries as flying penguins, hotheaded naked ice borers,

and Tasmanian mock walruses. And find a whole host of unnamed zany Welsh creatures here, described by Robert Graves.

For the moral of this post I will quote Dr. Seuss: From there to here, from here to there, funny things are everywhere! A Pro Tip for explorers of the Realms of the Imagination is never to be surprised by anything - but by all means take delight in everything.

What’s your favorite zany creature? Or, if you really want to make Z earn its keep as the final letter in the A to Z Challenge, what’s your favorite creature of them all?

[Pictures: Wapaloosie (Ever Climbing), rubber block print by AEGN, 2019;

Tripodero, and Roperite, illustrations by Coert Du Bois from Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods by Cox, 1910 (Images from Lumberwoods);

Marginalia, illuminations from Luttrell Psalter, 1325-40 (Images from British Library),

and “Maastricht Hours,” 1300-1325 (Image from British Library);

and “Maastricht Hours,” 1300-1325 (Image from British Library);

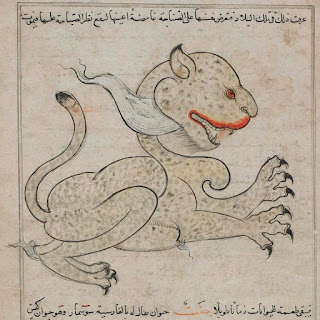

Kamikiri, painting from Bakemonozukushie (scroll version), before 1868 (Image from Internet Archive);

Dijiang, detail of wood block print by Jiang from Shan hai jing, 1628-44 (Image from Harvard Library);

Yop, illustration from One fish two fish red fish blue fish by Dr. Seuss, 1960;

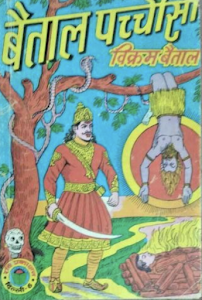

Capybureau, rubber block print by AEGN, 2018 (sold out).]