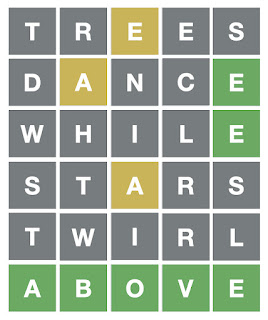

[Pictures: Wordle Lits by AEGN, 2022.]

June 29, 2022

Words of the Month - Wordle Lit

June 24, 2022

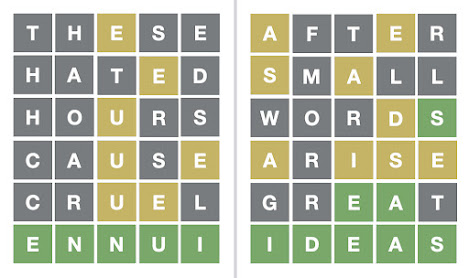

Who Is Catching Whom?

[Picture: Big Catch, rubber block print by AEGN, 2022.]

June 20, 2022

Juneteenth

[Pictures: Magic People, linoleum cut by Elizabeth Catlett, 2002 (Image from Cleveland Museum of Art);

Innervisions 2 (Unfurling), relief block print by Deborah Grayson (Image from GraysonStudios.com);

Liberty, linoleum block print by Peter Paul Piech, 1971 (Image from V&A).]

June 15, 2022

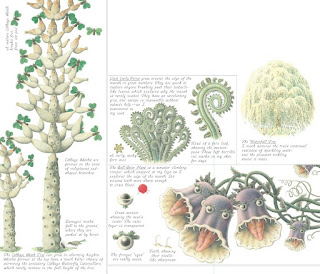

Fantasy Botany

[Pictures: Mandrake, wood block print from Ortus sanitatis by Johann Prüss, 1499 (Image from Internet Archive);

My Lady’s Garden, color wood block print by Walter Crane from The Baby’s Opera, printed by Edmund Evans, c 1877 (Image from International Children’s Digital Library);

Mary, Mary, illustration (possibly by Howard Del?) from Mother Goose’s Melodies for her Little Goslings, 1881 (Image from International Children’s Digital Library);

Two plants from Voynich Manuscript, c 1401-1599 (Image from Yale University Library);

Illustrations from Codex Seraphinianus, by Luigi Serafini, 1981;

Illustration from The Land of Neverbelieve by Norman Messenger, 2012.]

June 10, 2022

Shining the Light through Block Prints

[Pictures: Stained glass from Yale’s Humanities Quadrangle, 1932 (photos by AEGN, 2022);

Der Formschneider, wood block print by Jost Amman from Eygentliche Beschreibung aller Stände auff Erden, 1568 (Image from Yale University Library);

Theatrum, wood block print from Comoediae by Terence, 1493 (Image from National Gallery of Art);

Title Page, wood block print from Libre de consolat tractant dels fets maritims, 1502 (Image from Sotheby’s);

Trevithick’s Locomotive, wood engraving (by H.W. Benno?) from The Progress of Invention in the Nineteenth Century by Edward W. Byrn, 1900 (Image from Internet Archive).]

June 6, 2022

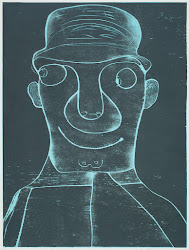

Picasso Poster

[Picture: Exposition Vallauris, linocut by Pablo Picasso, printed by Imprimetie Arnéra, 1956 (Image from AEGN, at the National Gallery of Scotland).]