Not surprisingly, we have lots of words with their origins in stories, especially the names of characters. Widely-known stories are cultural touchstones that offer us metaphors to describe all kinds of people, so they’re an obvious place to derive new words. As an author you know you’ve arrived when your characters become words in their own right!

Many of these words remain rooted to this day in their stories of origin.

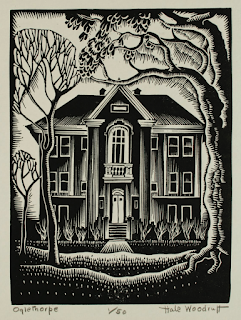

romeo - (often capitalized) a handsome, passionate male lover. Everyone knows this comes from Romeo Montague in William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet written in the 1590’s. The OED lists its first usage as a general word in 1766. (As for me, I can’t hear it used as a common noun without starting to sing Deniece Williams’s “Let’s Hear It for the Boy.” Get your ‘80s on with the video here.)

scrooge - miser and general sourpuss. This is still widely recognized as hailing from Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’s 1843 A Christmas Carol. It was fully genericized by 1905. (Prior post about this spec fic story here.)

grinch - curmudgeonly spoilsport. The story of grinch is similar to scrooge - both inside and outside the covers of a book. It comes straight from How the Grinch Stole Christmas by Dr. Seuss in 1957, and the animated television special from 1966. (I see that there’s a sequel - by other authors of course - scheduled for release this fall, which strikes me as a hideous idea - but maybe I’m just being a grinch about it.)

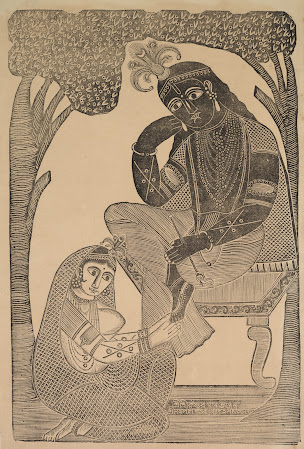

Prince Charming - the perfect romantic partner to live happily every after with. Everyone knows this comes from fairy tales… but what fairy tale exactly? The most likely beginning is Madame d’Aulnoy’s literary fairy tale “The Blue Bird” (1697) featuring “Le roi Charmant,” which Andrew Lang translated as King Charming in 1892. In Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Snow White says “the prince was charming,” but that’s never his name. In short, it looks like by the time the term actually appeared, it was already being satirized as a stereotype.

Other words come from fictional sources that might no longer be quite so widely read or recognized any more.

catch-22 - a dilemma in which one is trapped by contradictory conditions. This comes from Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 (1961) and entered common usage after the 1970 movie based on the book.

malapropism - the ludicrous misuse of a big, learned word. This one derives from Mrs. Malaprop in the play The Rivals by Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1775). Sheridan derived the character’s name from mal à propos, French for “inappropriately,” or literally “badly for the purpose.”

lothario - seducer, womanizer. “The gay Lothario” was a character in the play The Fair Penitent by Nicholas Rowe (1703). We sure do seem to love our womanizing literary characters. While we’re at it, let’s add Don Juan (popularized in English by Lord Byron’s poem in 1819) and even philanderer (from Philander, a stock character name for a lover, giving us the verb philander by 1737 and the noun by 1816).

paparazzi - freelance photographers who aggressively pursue celebrities. The singular is paparazzo, which is the name of a photographer in Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita.

Obviously any story that gave the language a word must have been wildly famous at the time, but some of them have sunk much farther into obscurity than others. Did you know the fictional origins of the following? Or even if you knew their origins, how many of these stories have you actually read?

fedora - a type of hat. This is named for the character Fédora from the play by the same name by Victorien Sardou. In the 1882 performance Sarah Bernhardt wore such a hat, and by about 5 years later (with the play still running) the character had given her name to the headgear - which eventually became a men’s hat after the Prince of Wales began wearing them in 1924.

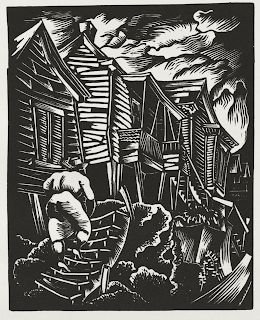

goody two-shoes - an excessively virtuous person or do-gooder. Published in 1765 by John Newbery (of Newbery Medal fame), The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes was a variation of a Cinderella story by an anonymous author, in which the virtue of a poor orphan girl is rewarded. For over a hundred years it was one of the most widely circulated books for children in both Britain and America. The thing I find most striking about the history of this word is how viciously we’ve turned a praise of virtue into a withering insult. (And if you want to continue your ’80s binge, with another twist on the stereotype, you could try Adam Ant’s song here.)

pollyanna - excessively cheerful or optimistic person. Pollyanna Whittier is the hero of Eleanor Hodgman Porter’s 1913 novel Pollyanna, and the word was being applied to optimists by 1921 after the book was adapted into a movie starring Mary Pickford. In the novel Pollyanna uses her optimism as a way of coping with the difficulties in her life, but of course nowadays we’ve once again turned the positive negative, and the only place you’ll ever hear the word used is when someone declares, “I’m no pollyanna.”

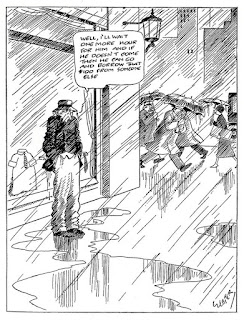

milquetoast - a weak, timid person (usually man). It can also be used as an adjective. Caspar Milquetoast was a character in The Timid Soul, a cartoon created in 1924 by Harold T. Webster. The cartoon ran for almost 30 years and was, according to Time magazine in 1945, as famous as Tom Sawyer. Webster derived the character’s name from “milk toast,” which is bland, harmless invalid food.

Although I’ve been referring to all these sources as literary, most of the authors didn’t manage to get their words into common usage through the printed page of books alone. You’ll notice that most come from plays, or were popularized by movies or movie and television adaptations. Scrooge and Milquetoast had popular newspapers and magazines to deliver them into every household. It’s not just any fictional character who can become a household word. It takes reach, as the marketers say, and an especially iconic personality.

[Pictures: Romeo and Juliet, wood engraving by Bellenger after F. Dicksee, 1864-8 (Image from Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive);

Le roi Charmant, hand-colored wood block print from L’Oiseau bleu, 19th century (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

Goody Two-Shoes, wood engraving from The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes, 1768 (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

Caspar Milquetoast, drawing by Harold T. Webster, first half 20th century (Image from Hairy Green Eyeball).]