This weekend I will be at Roslindale Open Studios, always one of my favorite shows of the year, and back after covid-induced hiatus for the first time since 2019. I’m very excited, and hope to see huge crowds of past and future art fans! Because I’ll be there doing my best to be commercially enticing, and because I was talking a little bit about open versus limited edition prints with my fall printmaking class this week, I thought now was a good time to share a little summary of the concept of limited edition prints.

The edition is the number of pieces printed from a block. An open edition means that as many pieces will be printed as possible - as many as the block can produce before it wears down, and/or as many as there is a market for. This was the traditional practice for centuries in both Europe and Asia, when wood block prints were viewed primarily as a method of reproduction, and primarily as a mass market medium. (By the way, all this history is also true of intaglio techniques and other hand-made printing techniques, but I’m not bothering to mention them as much, since this blog focusses on relief block printmaking.) In many cases blocks that began to sustain wear and damage were actually re-carved in order to extend their life. You can see a bit about this in my previous post on the famous “Under the Wave at Kanegawa.” Blocks were often printed on demand, and sometimes reworked by other artists after the original artist’s death. Nowadays impressions made from the original version of a block, as supervised by the original artist, are of course considered more valuable - when it’s possible to confirm. But at the time it was mostly just a matter of what the market would bear.

Artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein, and Hans Leonhard Schäufelein all produced wood block prints as the equivalent of how poster or postcard reproductions of fine art are used today (as you can see in the linked posts). Images of saints, the Totentanz, and the Power of Women themes were popular mass market prints. After all, wood block printing was initially the only form of reproduction possible (followed by copper engraving, etching, lithography, etc.) Some media are more fragile than others, of course, but wood blocks are relatively robust. Certainly hundreds of impressions can be made without significant wear to the block, so there are fewer practical limits for wood block prints than for some other printmaking techniques. So why did the practice of limiting editions of woodcuts arise?

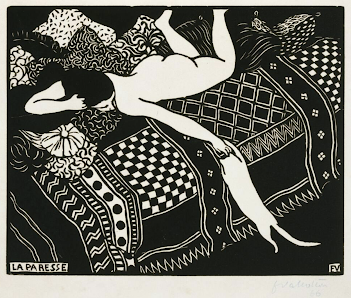

As various photomechanical methods of reproducing images were invented and refined throughout the 19th century, they became much cheaper and easier than the older methods that involved so much work done by skilled artists and artisans. Since relief printmaking was no longer considered the best method of reproduction, a number of artists in the west began reclaiming and exploring relief block printmaking as an artistic medium in its own right. Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Félix Vallotton, and later Matisse and Picasso began to make works that were conceived as wood and linoleum block prints, rather than mere reproductions of other media, and they explored the unique properties of the relief print medium. In Japan, too, by the middle of the 20th century there was a movement for artists to design, carve, and print their own works, rather than making designs which publishers then reproduced ad infinitum. (You can read more about this movement here.)

These artists working in relief printmaking were eager to make a distinction between their own works of art, made by hand by themselves, and the new methods of reproduction that used purely mechanical processes and did not require the hand of the artist. The idea of the limited edition helped artists show that their prints were works of original art, even if there were multiples, rather than mere reproductions. Both the scarcity of works in a limited edition and the reminder that each one is an original, contributes to their value. Limited editions allow artists to price their hand-made works higher than just the equivalent of a poster.

A limited edition print is labelled by the artist, usually in pencil below the image, and including the number of the piece within the edition and the total number in the edition (given as a fraction), as well as the artist’s signature. In older prints, using printmaking methods with large editions and gradual degradation of the plate, the lower numbers in an edition may be considered more valuable, but in modern printmaking there’s little substance to the idea. For one thing, editions are kept small enough that the block or plate doesn't wear down before an artists stops using it. For another thing, the ordering of the numbers may have nothing to do with the order in which each piece was actually printed. In my own case, after printing a whole bunch, I gather them all up, go through them, decide which ones are of sufficient quality to be included in the edition, and destroy all the others. I then number the whole edition, and by that point the pieces have been shuffled around so much that they could be in any old order.

Also, in general, the smaller an edition, the more valuable the prints are. Under this principle, my work is extremely valuable, because I make such small editions, usually only around 10. (On the other hand, I’m a small-time artist, so my work isn’t very expensive anyway!)

Nowadays lots of different products from Barbie dolls to cars may be produced in limited editions with this idea of raising the value of something through scarcity. But don’t forget that the real value of limited edition prints isn’t just the number, but the fact that each one is made by hand by the artist. (And a bit more about that at prior post “Original or Reproduction.”) So, are you ready to see some of my original limited edition prints this weekend? I’ll see you at Roslindale Open Studios!

[Pictures: Detail of Anchored in the Living Sea, rubber block print by AEGN, 2005;

La Paresse, woodcut by Félix Vallotton, 1896 (Image from The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston);

The Devil Speaks, woodcut by Paul Gauguin, 1893-4 (Image from The Met);

Bowl of Begonias I, linocut by Henri Matisse, 1938 (Image from Minneapolis Institute of Art).]

No comments:

Post a Comment

I love to hear from you, but please no spam, ads, hateful language, or other abuse of this community.