This wood block print comes from an incunabula (early printed book) by Rodrigo Sánchez de Arévalo, aka Rodericus Zamorensis (Spain, 1404-1470). Zamorensis wrote Speculum vitae humanae (Mirror of human life), published it in 1468 (possibly the first printed book by an author who was still alive at the time), and saw it become quite popular. It was quickly translated into several other languages. As for what the book was actually about, it discussed the pros and cons of various trades and walks of life, thus making it a valuable resource for the study of medieval society. For my purposes, however, the earliest editions are less interesting, because not until slightly later editions were illustrations included.

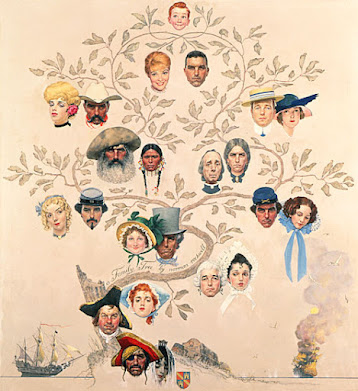

This full-page woodcut comes from a German edition from Augsburg c. 1475, and represents some sort of family tree. I’m not sure how it fits into the whole book, since this seems to be the only edition I see that includes it. I find it a marvelous wood block print. The level of detail is fantastic, with all the little people adorned with their identifying headgear and accoutrements, and the elaborately botanical vine that connects them all. It’s the only full-page illustration in the book, so it clearly warranted a special effort. The illustration is followed by five pages of a key to identify all the people. The first person, labelled A, is at the lower right corner, and he’s identified as Albrecht earl in Elbes, lord of Sassenburg. It’s a distinguished family, including plenty of dukes and duchesses and even kings and queens, plus at least one abbess and what looks like a pope or other high-level churchman. Many of the men hold swords, but some have staves or scepters, and I like the wide variety of headgear.

One thing I particularly appreciate is how many women are included in this family tree. I mean, logically any family tree should be about half and half, but all too often the women are invisible. Here we not only have what are presumably grandmothers and great-grandmothers, but also an array of daughters illustrated, as well as the names, dates, and estates of a number of wives included in the key for their husbands.

Ultimately my medieval German is far too weak for me to spend the time trying to decipher this whole thing to find out exactly who all these people are and how they relate each other, and to Zamorensis or his patrons. But while I enjoy history, that’s not really the point here. I like the picture for the infinite possibilities it suggests. It reminds me of Norman Rockwell’s famous “Family Tree” painting, in which he imagined all the varied ancestors whose lives came before an “ordinary American” boy. We’re all the product of hundreds and thousands of ancestors, whether we know who they are or not, and I love to think about all the people who came before - and how they had no idea of all the people who would come after, including me!

[Pictures: wood block print from Spiegel des menschlichen Lebens by Rodericus Zamorensis, c. 1475 (Image from Library of Congress);

Family Tree, painting by Norman Rockwell, 1959 (Image from Norman Rockwell Museum).]

This is fun I love me a good challenge - and my German is good enough to read this. I found your abess:

ReplyDeleteq: Katharina was eyn Äptissin zewien zu Sant Clara

q: Katharina was an abess, consecrated (my guess) to saint Clare.

Which one do you see as a possible pope? Because all I can see are kings or dukes (Herzog / Erzherzog) and even maybe a Roman emperor.

Yes, it's tt at the top who looks like a pope. His caption makes him Fridrich, archduke, and possibly a [holy] Roman Emperor. But the orb and sceptre and mitre are clearly ecclesiastical acoutrements and I don't know how that relates. Looks like it gives his birth date, so it should be possible to look him up and figure out who he actually is, but like I said, I don't have the time for a whole research project, tempting as it may be. =)

ReplyDeletePopes from back then would wear the triple tiara, not a mitre, that's modern ;) I'll look him up tomorrow and post my finds here, should be quite easy as you say wiht dates and names given.

ReplyDeleteYour tt is Friedric III: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_III._(HRR)

ReplyDeleteThanks for looking that up. What fun to have him identified!

ReplyDeleteThis is fascinating! I wish I had an ear for languages. I could always read my Spanish and test out of many years in placement tests, but per conversation, I just wasn't on par with my over-the-counter set of ears I inherited. But that is neither here nor there. I am gobsmacked by this print. Graphic representations of personal and social relationships of men and women, and generations, are new to me. Paintings are the forms with which I am most familiar. Graphic images communicate in ways that written words cannot. Now I have to think about the depiction of information through block prints with the advent of books. Not everyone could afford the color of oil painting portraiture nor the hand illumination of pages in individual copies of books. Now I have to think about the sociocultural changes to graphics that the printing press wrought.

ReplyDeleteNancy, thanks for stopping by! Block printing definitely democratized things in some ways, although of course it would still be only elites being featured in books. But all sorts of art and images became available to a pretty wide range of society through books, but also through inexpensive images of Biblical and popular figures and stories. You might be interested, for example, in the prints illustrating the Power of Women: https://nydamprintsblackandwhite.blogspot.com/2018/03/the-power-of-women.html

ReplyDelete