Pages

February 28, 2022

Words of the Month - Naked Babies with Wings

February 23, 2022

William E. Smith's Linoleum Prints

[Pictures: My Son! My Son!, linoleum cut by William E. Smith, 1941;

War Fatigue, linocut by Smith, 1940;

Poverty & Fatigue, linoleum cut by Smith, 1940 (Images from Cleveland Museum of Art and The Melvin Holmes Collection of African American Art).]

February 18, 2022

Sledding Squid

• Art Show (60 pieces!)

• Presenting my talk “The Fantastic Bestiary” (always a little stressful wondering whether the tech will work)

• Panel of artists talking about “Different Artists, Different Mediums”

• Panel of authors talking about “Scary Fairies”

• Panel of authors talking about “Poetry Matters”

• Broad Universe Rapid-Fire Reading (much dithering over what to read, but I’ve finally chosen an excerpt)

• Drop-in workshop where people can make mini block prints

[Squids love sledding, color linoleum block print by Sarah Smith, 2015 (Image from Dartmouth Library Muse);

Packed up artwork, photo by AEGN, 2022.]

February 14, 2022

How to Make a Love Potion

[Pictures: Love Potion, rubber block print by AEGN, 2021 (first published in Periodic Table of Alien Species (Elements 1-86) by Miguel O. Mitchell);

Ineffable Feathersquid, digital illustration by AEGN, 2022 (first Published in Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores, Feb. 2022).]

February 9, 2022

The Brass Horse

They murmured, as doth a swarm of been,

And made skills after their fantasies,

Rehearsing of the olde poetries,

And said that it was like the Pegasee,

The horse that hadde winges for to flee;

Or else it was the Greeke's horse Sinon,

That broughte Troye to destruction,

As men may in the olde gestes read.

Mine heart," quoth one, "is evermore in dread;

I trow some men of armes be therein,

That shape them this city for to win:

It were right good that all such thing were know."

Another rowned to his fellow low,

And said, "He lies; for it is rather like

An apparence made by some magic,

As jugglers playen at these feastes great."

Of sundry doubts they jangle thus and treat.

As lewed people deeme commonly

Of thinges that be made more subtilly

Than they can in their lewdness comprehend;

They deeme gladly to the badder end.

So many heads, so many wits, one sees.

They buzzed and murmured like a swarm of bees,

And played about it with their fantasy,

Recalling what they'd learned from poetry;

Like Pegasus it was that mounted high,

That horse which had great wings and so could fly;

Or else it was the horse of Greek Sinon

Who brought Troy to destruction, years agone.

As men in these old histories may read.

"My heart," said one, "is evermore in dread;

I think some men-at-arms are hid therein

Who have in mind this capital to win.

It were right well that of such things we know."

Another whispered to his fellow, low,

And said: "He lies, for it is rather like

Some conjured up appearance of magic,

Which jugglers practise at these banquets great."

Of sundry doubts like these they all did treat,

As vulgar people chatter commonly

Of all things that are made more cunningly

Than they can in their ignorance comprehend;

They gladly judge they're made for some base end.

This steed of brass, that easily and well

Can in the space of one day naturel

(This is to say, in four-and-twenty hours),

Whereso you list, in drought or else in show'rs,

Beare your body into every place

To which your hearte willeth for to pace,

Withoute harm to you, through foul or fair.

Or if you list to fly as high in air

As doth an eagle, when him list to soar,

This same steed shall bear you evermore

Withoute harm, till ye be where you lest

(Though that ye sleepen on his back, or rest).

[Pictures: There came a knight upon a steed of brass, illustration by Walter Appleton Clark, 1914 (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

The Ebony Horse, linocut and woodcut by Bill Reily, 1960 (Image from theMcNay);

Ebony Horse, frontispiece by John Dickson Batten from More Fairy Tales from the Arabian Nights, 1895 (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

Mounting the Ebony Horse, illustration by Marc Chagall from Four Tales from the Arabian Nights, 1948 (Image from Indianapolis Museum of Art).]

And the rest of the versions I've excerpted above, here and here.

February 5, 2022

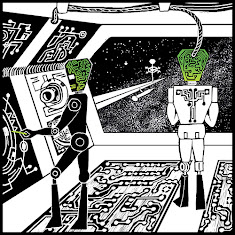

A Robot

[Picture: The Robot, color woodcut by Werner Drewes, before 1971 (Image from Smithsonian American Art Museum);

Starbase Sector's End (Gallium), faux woodblock by AEGN, 2021.]