Humans love stories of lost cities. I guess it just seems so much more likely that something is merely lost than that it has never existed at all. But we have many different lost city legends, that serve many different purposes for us: Atlantis warns us about hubris, Shangri-La promises us paradise, Kitezh assures us that virtue is rewarded… and El Dorado caters to our unbridled avarice.

The word El Dorado, “the golden one,” originally referred to a person, a chief of the Muisca or Chibcha people of Columbia. This king was said to participate in an initiation rite in which he was covered head to toe in gold dust, and threw vast quantities of gold and emeralds into a sacred lake as offerings. Clearly, reasoned the sixteenth century Spaniards, anyone practicing this sort of ritual had more gold than he needed. The legend grew and morphed into conviction that there must exist a city and possibly an entire empire of unimaginable wealth. (And as Han Solo would say, the Spaniards could imagine quite a bit.) The name El Dorado morphed with the legend, and fueled centuries of greed-crazed expeditions.

There are some tantalizing facts associated with the legends. Much of the search for El Dorado over the years focussed on the lake where all the gold offerings were dumped. Lake Guatavita is one candidate, which was found by conquistadores in 1537. They attempted to drain the lake in 1545 with a bucket chain, and a second attempt was made by a Bogatá business entrepreneur in 1580 by cutting a notch in the rim. Each attempt recovered some gold, but not what they had hoped for. In 1898 a British firm dug a tunnel up from the bottom and drained the lake like pulling the plug on a bathtub… Except that there remained four feet of mud at the bottom, which then set hard and made it impossible to dig up anything. They recovered even less than the others. As of 1965 the poor lake is refilled (at least up to the level of the notch) and is a protected area.

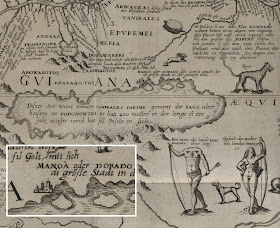

The other much-sought lake, Lake Parime, was believed by Sir Walter Raleigh to be the site of El Dorado (aka Manoa). It appears on many old maps, but by the nineteenth century was concluded to be a myth. Interestingly, Brazilian geologists in the twentieth century discovered evidence that there had indeed once been a large lake in that area. Possibly an earthquake in 1690 opened a fault that eventually emptied the lake completely. As far as I know, however, significant quantities of gold and emeralds have not been found at that site, either. Perhaps it all washed away as the lake drained.

About a year or so ago D and I watched a documentary which theorized that the Muisca people had so much gold not because they lived in a land of gold, but because they became wealthy by producing salt which they sold to everyone else in the region. They valued the gold not as earthly currency, but as divine currency: the requisite offering to the gods. It was pretty interesting and I think it must have been “Secrets: Golden Raft of El Dorado” by Smithsonian Channel, if you’re interested.

At any rate, what’s fascinating about the legend of El Dorado is that it reveals just how incredibly powerful a force for fantasy our greed is. No matter how outrageous the story, we long to believe it if it promises us “easy” wealth. Think of the effort people will go to, the lives ruined, lost, and stolen, the money wasted, the laws broken, the tyrants and swindlers followed, the archaeological artefacts destroyed, the lands despoiled… all because we just can’t seem to stop ourselves from believing in the fantasy that somewhere out there is infinite wealth for the taking. It’s certainly not our finest trait, nor the noblest use of our imaginations, but there’s no denying it’s a strong component of that infuriating mix that is humanity.

(My A-to-Z post about El Dorado, with some modern images, here.)

[Pictures: Muisca raft, pre-Columbian gold sculpture of the El Dorado ceremony, c 600-1600 CE (Image from Historic Mysteries);

Laguna de Guatavita, engraving by Eustacio Barreto from Papel Periódico Ilustrado, 1882 (Image from Banco de la República Columbia);

Map showing El Dorado on the bank of Lake Parime, engraving by Theodor de Bry from Grands Voyages: Americae pars VIII, 1599 (Image from Library of Congress);

King of Guaiana being covered with gold dust, engraving by Theodor de Bry from Grands Voyages: Americae achter Theil, 1599 (Image from Library of Congress).]

Great accompaniment to your A-Z post!

ReplyDelete