One common type of cliché or idiom is pairs of near synonyms that habitually appear together. We really wouldn’t need both words for meaning, as the two words mean something similar and related, and sometimes even the same thing — but they just sound so right and proper together. (See what I did there?)

Some of these pairs date all the way back to the twelfth through fourteenth centuries and include a word from Old English roots together with one from Norman French roots.

Examples include

Examples include

right and proper

law and order

love and cherish

safe and sound

tried and true

bits and pieces

strait and narrow (now, alas, commonly misinterpreted as “straight and narrow,” which of course aren’t synonymous)

The theory is that during the period when French and English were both spoken in England (more linguistic info here), such pairings increased the chances of understanding. It may indeed be true that the bilingual situation added impetus to the practice, but there are certainly lots of other common pairings, for example

part and parcel - both words from French roots

house and home - both words from Old English roots (more here)

wit and wisdom - both words from Old English roots

And of course we have lots and lots of pairings that didn’t appear until long after the Norman Conquest. So why are phrases of this type so common in English? I don’t know. It seems that English simply loves its coupled words.

Some pairings are especially nifty because they include fossil words. A fossil word is one that has disappeared from the language except in frozen phrases, such as

vim and vigor - People do sometimes now speak of vim, but only when they’re consciously taking it out of its accustomed phrase for humorous intent.

spick and span

kith and kin - Kith was, in fact, not a synonym of kin. The phrase can actually be defined by another familiar clichéd pairing: friends and family.

hem and haw - The hem is certainly uncommon on its own, although it appears as onomatopoeia whenever Dolores Umbridge clears her throat, but the haw, meaning “to hesitate” is throughly fossilized.

beck and call - Although beck is no longer a word on its own, you can see its relation to beckon.

Will narrow’s strait soon be a fossil, too?

Interestingly, legalese seems to love its repetition particularly, perhaps because it’s thought to be more precise or to eliminate ambiguity? Or perhaps just because it’s more pretentious!

aid and abet

cease and desist

null and void

pain and suffering

There’s no exact term for these pairings, by the way. They are examples of binomials, but binomials also include other sorts of customary pairings that aren’t synonymous, including “cap and gown,” “through thick and thin,” and “bacon and eggs.”

I’ll go above and beyond and give you a few more binomials that are needlessly repetitious, but which just seem to go together so nicely. Note how common alliteration is in helping these pairings sound good together.

hide nor hair

fast and furious

ways and means

lord and master

hale and hearty

prim and proper

rant and rave

trials and tribulations

alive and well

each and every

fuss and bother

odds and ends

bag and baggage

footloose and fancy free

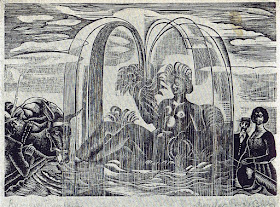

[Picture: Baroque Fountain, wood block print by Douglas Percy Bliss (Image from The New Woodcut, Malcolm C. Salaman, 1930). And no, there’s no connection with the day’s theme, but how do you make a picture of “tried and true”?]