I’m always getting curious about random words that catch my attention, and looking up their etymologies. It happened to be a strange coincidence that a bunch of words I recently looked up were all food words that started with the letter C, and so, my friends, we have ourselves a theme. Since there’s really no more method behind my madness than that, let’s get started without further ado.

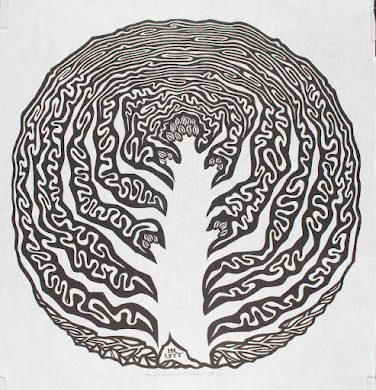

cabbage - English gained this word in the mid-fifteenth century from a French dialect, and to talk about a head of cabbage is redundant as cabbage simply means “head.” (In fact there are an enormous number of words that derive from the same Latin root, so here are some of them with their own Words of the Month theme.)

canapé - The French were using this word for finger foods by the late eighteenth century, and it seems to have been borrowed by English about a hundred years later around 1890, although possibly not really embraced until the era of speakeasies and cocktail parties. The literal meaning of the word, however, is “canopy.” So what’s the connection between fancy little sandwiches and a suspended covering providing shelter? Well, since Roman times canopies were often suspended over couches or sofas as protection against insects, which meant that many of the Romance languages adapted the word “canopy” to refer to the couch. Then somewhere along the line the word for couch was applied to the foods that are convenient to eat while seated on a couch instead of around a table - and are made by “seating” various toppings on bread or crackers. So our canapés are really named after sofas that are named after canopies.

chutney - English-speakers borrowed the Hindi word chatni in 1813, along with the condiment itself. The etymology of the Hindi word is “to lick” or “eat with an appetite.” I certainly am happy to lick up a good chutney!

clove - Another food used to add flavor, cloves are a spice made from the dried buds of the clove tree. The shape of those dried buds gives them their name, which comes from the Latin clavus meaning “nail,” (by way of Old French, of course).

Cloves of garlic, on the other hand, are completely unrelated. That word goes all the way back to Old English, and ultimately from a root meaning “a thing that is cleft or cloven,” because of the way a bulb of garlic is divided into those separate cloves.

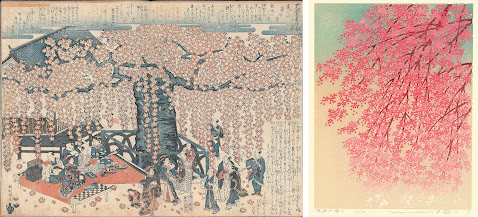

chestnut - The nut in chestnut, which appeared in English as chesten nut around 1510, is another redundancy, as the chesten part already meant “chestnut” (from French, from Latin, from Greek). The Greeks probably borrowed the word from some language of Asia Minor, where the trees famously grew. By the way, the secondary meaning of chestnut, “an old, well-known joke or anecdote” probably comes from the play “The Broken Sword” by William Dimond, in which two characters disagree over whether it’s a cork tree or a chestnut tree that features in story heard for “the twenty-seventh time.”

chai - While we’re on the subject of redundancy, “chai tea” is another one, since chai means “tea” in Hindi, which borrowed the word from Chinese cha. (English tea is also ultimately from Chinese, though the form comes by way of Dutch, by way of Malay or Min Chinese.) The reason chai in English refers to spiced tea, rather than plain tea, is that we borrowed both word and beverage as masala chai, which means “mixed-spice tea.” It’s the most recent of today’s acquisitions, not becoming widely used in English until the 1990s.

cappuccino - And while we’re on the subject of fancy beverages that didn’t become popular in English until the twentieth century, this espresso coffee drink is named for Capuchin monks, an order of Franciscans. Capuchin means “little hood,” a part of the monks’ habit. The coffee, however, is named for the color of these hooded robes, a reddish-brown that apparently is what you get when you add a little milk or cream to an espresso. (I wouldn’t really know, as I’d pick chai any day!)

I hope you enjoyed this little tasting of C foods! And the next time you partake in one of them, take a moment to savor the joys of etymology and the history it preserves.

[Pictures: Red Cabbage, wood block print by Jacques Hnizdovsky, 1971 (Image from HMML Art Collection);

Sweet Chestnut, wood engraving from Nouveau dictionnaire encyclopedique universel illustre, 1885 (Image from OldBookIllustration);

Cappuccino Coffee, linoleum block print by Meg, 2019 (Image from her Etsy shop WanderingStarPrints).]