(My A to Z Blog Challenge theme this year is How to Make a Fantastical Creature, in which I explore 26 traits that are widely shared among the monsters and marvels of fantasy and folklore.)

In nature, animals are morally neither good nor bad: they all just do what comes naturally to eat, breed, and keep themselves alive. But in unnatural history, creatures are almost always labelled as good or bad, and the really bad ones are often actually demonic. Mythology and folklore are full of strange and magical monsters that originate in hell or actively align themselves with pure Evil.

Mythology of many cultures around the world deals with forces of evil, although there is wide variation in how the whole cosmology of good and evil works. Are demons subservient to God; does God use demons for heavenly ends? Can one demon serve as protection against another demon? Do demons have free will? Can humans summon and command demons using magic? Were demons created evil, or are they fallen from a divine creation? Despite all the various ways these questions can be answered in different cultures, there are some common threads that show up with some frequency: demons are often seen as forces of disease, and also forces of sin (ie negative behaviors and disorders). They are often believed to be able to possess humans, rather than merely acting on them. It is also the case that “demons” is frequently considered a general category including many undifferentiated individuals. Still, there are some particular demonic monsters I can highlight today.

The incubus is a kind of male demon who seduces/rapes sleeping women, while the succubus is the female equivalent. Usually they are portrayed as gorgeous humanoids, but often they have unsettling characteristics such as claws or tails. The Trauco (a dwarf with no feet) is an incubus who lives on an island in Chile, and the lidérc (who can take the form of a will o’ the wisp - or of a naked chicken!) lives in Hungary. Incubi and succubi are ever-popular in folklore, because sex.

In South Africa the impundulu or lightning bird is a vampiric demon that summons lightning, serves as a familiar of witches, and can also behave as an incubus.

The Balrog of The Lord of the Rings is a winged demon of fire and shadow, armed with a flaming sword and a many-thonged whip. Tolkien gives the etymology of the name as Orcish for “cruel demon.” The giant spider Shelob also seems to be classed as a demon, rather than a mere monster.

The batibat of Tagalog folklore is a huge, obese tree-spirit demon, who becomes vengeful when her tree is cut down, and may suffocate people, or torture them through dreams.

In Bali Rangda is a demon queen who eats babies and brings disease, and is eternally battling the forces of good.

One of the most famous Judeo-Islamic-Christian demons is Asmodeus, who, depending on who’s telling, ranges from “the worst of demons” who murders anyone he gets his hands on, to one that can be bound by Solomon to build the temple and do other odd jobs. He’s often said to be a demon of lust, but also gets credited at various times with vengeance and gambling. Sometimes he’s portrayed as a handsome man who limps due to one rooster foot. Other times he’s a little more interesting: in addition to the rooster leg, he has a serpent tail and three heads: a sheep, a bull, and a man spitting fire. He appears as a character in tons of modern stories, but I won’t even get started on all the demons of modern fiction, D&D, and various computer/video games.

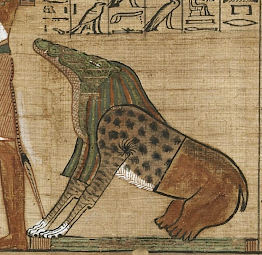

Ammit (introduced under the letter C) is also often classed as demon, although in ancient Egypt the distinction between demons and gods could be fuzzy. The wendigo (introduced under A) can also be classed as a demon. Plus, you can check back in previous posts for snippets on Bartimaeus, the tormentors of St Anthony, imps, Tibetan demon Mara, Persian demon Falud-zereh, Japanese oni, and the Alpine Krampus.

Because this is the last post of the month, let’s spend a little time on etymology. The word demon appeared in Middle English around 1200 from the Greek daimōn. The Greek word referred to a minor deity, a divine spirit lower than a god, or a guiding spirit. It had no negative connotations. Its English meaning of a spirit of pure evil arose because Greek translations of the Bible (both Christian and Jewish) used the word daimōn for “heathen gods and idols,” and “unclean spirits.” So as the word was absorbed into English, it came with that connotation. But around the mid-sixteenth century English went back to the Greek and re-borrowed the word in its original sense of a guiding spirit. It’s usually spelled daemon or daimon when it’s used that way.

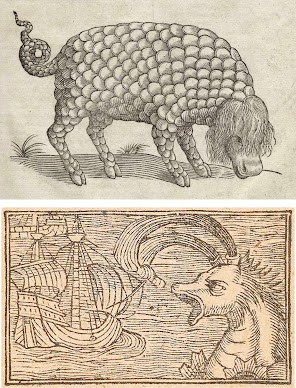

This etymology helps illustrate that your views on demons (even taking the modern English definition of “a spirit of evil”) will be influenced by your culture. Lamashtu is a

dreadful demon of ancient Mesopotamia. With a lion head, donkey ears, hairy body, and talons for feet, Lamashtu particularly loves to kill babies and pregnant women. On the other hand, she can be warded off by invoking other demons, particularly Pazuzu, with a canine head, horns, a scorpion tail, and two sets of wings. Pazuzu is certainly a scary and dangerous being, but he obviously has his uses. (Also in Mesopotamia, Gallu demons dragged their victims down to the Underworld, and the demon Asag was so monstrous that his presence made fish boil alive in the rivers, which I think is a marvelously horrible description.)

The obvious moral of demons is that you must stay strong and vigilant to withstand the temptation to evil. A Pro Tip for exorcists is that sometimes you can summon one demon to get rid of another. On the other hand, sometimes that strategy ends up like The Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly: she died, of course. It’s probably wise to have bell, book, and candle at the ready just in case things get out of hand. A shofar and Thibetan Guthuk soup can also be efficacious.

The nature of Good and Evil - that really is THE question, isn’t it?

[Pictures: Incubus (The Nightmare), oil on canvas by Henri Fuseli, 1781 (Image from Detroit Institute of Arts);

Balrog, film still from “The Fellowship of the Ring” directed by Peter Jackson, 2001 (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

Impundulu, illustration by Ken Wilson-Max, 2013 (Image from the artist’s web site the Illustrationist);

Rangda, wooden mask from Bali (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

Asmodeus, engraving by M.L. Breton from Dictionnaire infernal by Collin de Plancy, 1863 (Image from Library of Congress);

Lamashtu amulet, carved stone, Babylonian, c 7-6th century BCE (Image from Met Museum);

Divs, illumination attributed to ‘Ali Quli, from the Khamsa of Amir Khusraw Dihlavi, c 1598 (Image from The Walters Art Museum).]