A ghost word is a word that makes it into a dictionary or authoritative work by mistake, and having once landed there is taken by everyone to be a real word. The essence of a ghost word is that it had no meaning or usage at all before mistakenly being given a place in a position of authority. Most ghost words are eventually unmasked and removed from dictionaries, but some stick around a surprisingly long time. I’ve chosen this topic for this month’s Words because there’s a ghost word associated with one of my mythical X creatures.

hsigo - “flying monkey from Chinese mythology,” this word was apparently a mistake generated by optical character recognition software trying to read hsiao (which I featured under the alternate Romanization xiao, because x’s are always more exciting.) Having once appeared in Wikipedia, the word can now be found all over the web, and although Wikipedia has been corrected, it’s probably too late - the hsigo has escaped from captivity and is naturalizing on the internet.

hsigo - “flying monkey from Chinese mythology,” this word was apparently a mistake generated by optical character recognition software trying to read hsiao (which I featured under the alternate Romanization xiao, because x’s are always more exciting.) Having once appeared in Wikipedia, the word can now be found all over the web, and although Wikipedia has been corrected, it’s probably too late - the hsigo has escaped from captivity and is naturalizing on the internet.

dord - “density,” added to Webster’s when the abbreviation D or d was mistakenly taken as a word in its own right. It existed as a word in all the Webster’s editions from 1934 until 1947.

phantomnation - “multitude of spectres, illusion,” added to dictionaries in the eighteenth century when Alexander Pope’s “Phantome-nations of the dead” was copied without its hyphen and came to be reinterpreted as a single word.

morse - “to prime or foster,” first appeared in nineteenth century editions of Walter Scott’s novel The Monastery in the line “dost thou so soon morse thoughts of slaughter?” A scholarly journal included articles giving etymologies of morse (from French amorce in priming a musket, or from Latin mordere in biting or gnawing). In fact, however, it was simply a misprint of nurse, as eventually confirmed in Scott’s original manuscript.

ouphe - “imp, goblin, elf,” another of my mythical creatures, and probably simply a misspelling or misprint of oaph/oaf. The word first appeared in Shakespeare, which is why its existence was considered authoritative. (Alexander Pope and Walter Scott are not so widely popular these days, but they, too, were major bestsellers and trend-setters in their days.)

feamyng - “a group of ferrets,” appeared in several dictionaries including a 1949 crossword dictionary. Although it looks like a most satisfactory Old English word, it is, apparently, merely the final result of a long string of errors gradually transforming busyness to feamyng. The proper collective term for ferrets is therefore a “business.”

snalce - “one who schemes, connives, and uses sex appeal to further their own ends.” Okay, this word doesn’t actually appear in any dictionaries, although it should. It’s a word in usage among my friends and family, and it originated from my misreading of a friend’s handwriting when, in a high school note, she described a certain scheming classmate as a “snake.” If snalce ever does get into the dictionary, of course, it will be a simple coinage rather than a mistake, but its origins are purely ghostly.

esquivalience - “the willful avoidance of one’s official responsibilities,” is not technically a ghost word because it was invented for The New Oxford American Dictionary deliberately in 2005, as a copyright trap. Copyright traps are minor “mistakes” or falsehoods purposely included in reference works in order to provide evidence of plagiarism should they be copied. However, like ghost words, they can potentially be taken as real words despite having no linguistic past.

The term ghost word was coined by Walter William Skeat in 1886 in an address to the Philological Society , in which he praised OED editor James Murray for trying to eliminate such words from the dictionary. Personally, however, I think they’re fun. And chances are that a few of the words we use today might well have begun with a copyist's or editor's error that never was caught.

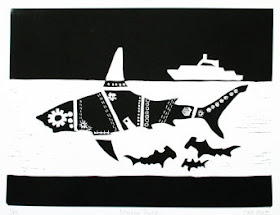

[Pictures: Midnight, linoleum block print by Lori Biwer-Stewart (Image from her Etsy shop);

Ferrets, linocut from Etsy shop Indrukwekkend (Image via Pinterest).]